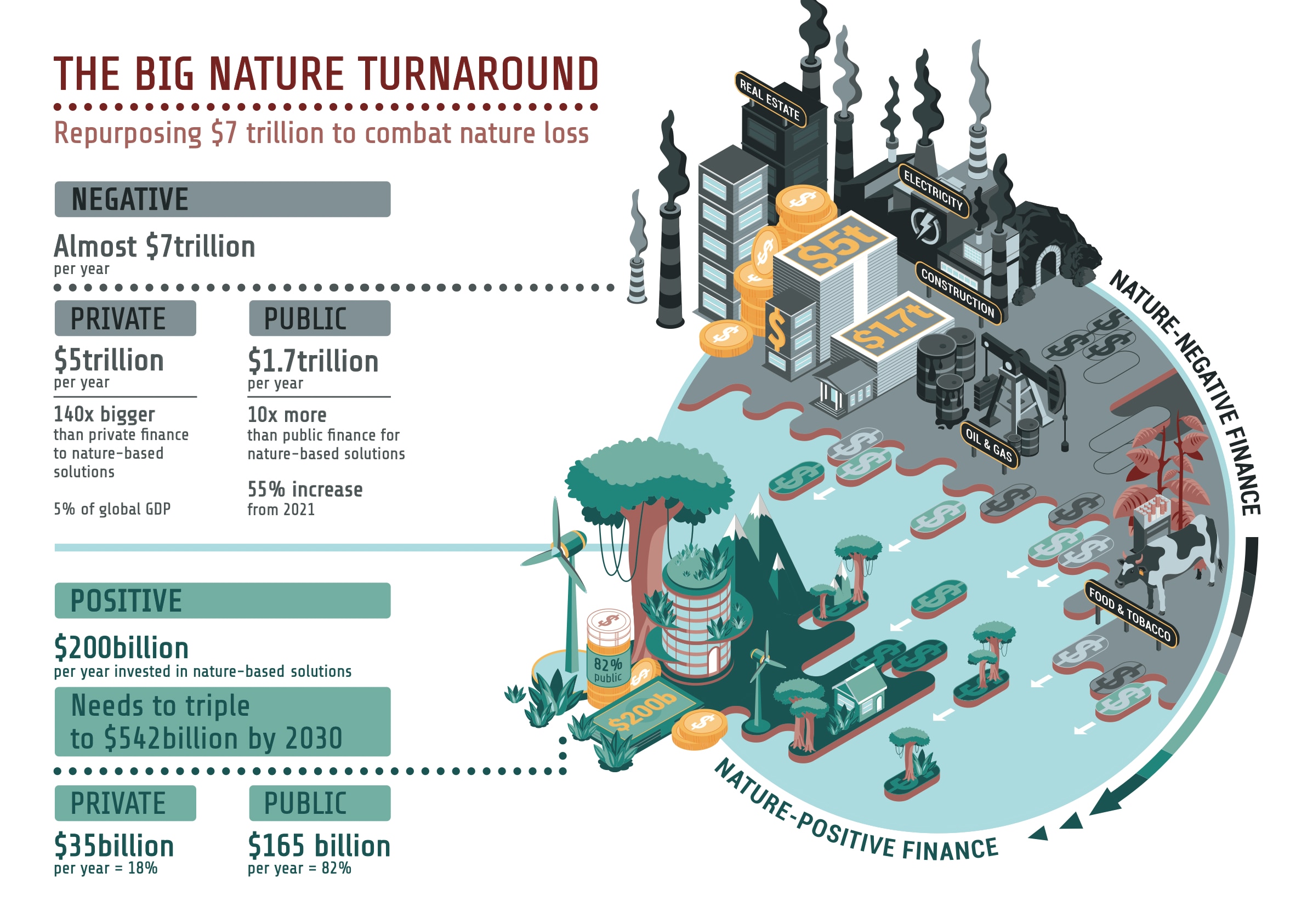

The integration of financial mechanisms to support biodiversity conservation has gained momentum, with a recent report by the World Economic Forum and McKinsey & Company identifying 10 high-potential models to channel capital toward nature-positive outcomes. As economic systems face increasing risks from ecosystem degradation—half of global GDP is exposed to nature loss—these financial tools aim to align investment with environmental sustainability. The report, titled Finance Solutions for Nature, evaluates 37 structures and narrows in on those with the greatest scalability and return potential. n nAmong the prioritized models are sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs), which tie borrowing costs to environmental performance. Uruguay’s 2022 sovereign SLB, linked to forest conservation and emissions reduction, attracted four times the demand expected, demonstrating investor appetite. Thematic bonds, such as Ørsted’s €100 million blue bond for marine restoration, direct funds exclusively to ecological projects, though clearer standards could enhance their effectiveness. n nSustainability-linked loans (SLLs) offer another pathway, with Iberdrola’s 2022 loan from BBVA tied to a 50% reduction in water withdrawals by 2030. Similarly, Tornator Oyj secured a €350 million green loan for sustainable forestry, highlighting the role of targeted lending. Impact funds like Silvania, a $500 million natural capital fund, take on higher risks to finance large-scale restoration and conservation across forests and coastal areas. n nEmerging models include natural asset companies (NACs), which monetize ecosystem services through equity. The first NAC, established by an Indigenous-led group on over a million acres, manages climate regulation and freshwater systems, though more transactions are needed to validate the model. Environmental credit markets, such as the UK’s Biodiversity Net Gain policy, require stronger standards and community involvement to ensure credibility. n nDebt-for-nature swaps (DNS) are gaining traction, as seen in Barbados’s 2024 agreement financing water resilience through performance-linked debt. Payments for ecosystem services (PES), like VEJA’s Amazon rubber program, incentivize conservation by offering premiums to suppliers—over 1,000 tonnes were purchased by 2021. Internal nature pricing (INP), still in early stages, mirrors internal carbon pricing; Microsoft’s carbon fee offers a precedent for embedding environmental costs into corporate decision-making. n nDespite progress, challenges remain. While nature-related private investment exceeded $102 billion in 2024, $7 trillion continues to fund activities harmful to ecosystems. Annual biodiversity financing needs to reach $700 billion, requiring coordinated action across public, private, and multilateral sectors. The report emphasizes five enabling actions, including standardization, risk mitigation, and stronger governance, to scale these solutions and close the funding gap. n— news from The World Economic Forum

— News Original —nNature finance models to meet global biodiversity goalsnNature finance is an emerging area of sustainable investing, but significant complexity is slowing progress in this area. n nA new World Economic Forum and McKinsey & Company report aims to consolidate existing guidance, identifying 10 priority models for nature finance. n nFrom sustainability-linked loans to internal nature pricing, these models could help mobilize capital for global biodiversity goals and a transition to a nature-positive economy. n nNature finance has moved from the margins of sustainable investing into a core area of focus in recent years, according to a new World Economic Forum report. n nFinance Solutions for Nature, produced in collaboration with McKinsey & Company, examines how to effectively mobilize capital for nature. As interest in nature finance grows, it’s essential to acknowledge the complexity that remains, with fragmented biodiversity data and nascent links between climate and nature finance being just two challenges for investors to overcome. n nThere is also a persistent gap in how nature is valued in economic and financial decisions. It’s estimated that half of global GDP is at risk of disruption as a result of nature loss. Reinforcing this, the Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025 identifies biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse as the second greatest global threat of the next decade. n nFinance Solutions for Nature aims to help boost investor confidence in nature finance by consolidating existing guidance. It explores 37 financial solution structures, but focuses on 10 priority solutions with high potential to mobilize capital for nature and deliver investible returns. They range from the familiar, such as sustainability-linked bonds and impact funds, to frontier solutions like natural asset companies and internal nature pricing. n nEach solution has different strengths depending on context, but they all stand out for their potential to deliver nature outcomes, at scale, with investable returns. n nThe 10 priority solutions n nSo what are these solutions, the key actions required to achieve them at scale and their real-world applications? n n1. Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) n nThese are commercial bonds that tie coupon rates to nature-related targets, for either corporates or governments. To scale, they will require stronger triggers, clearer metrics and closer alignment between issuers and investors. n nUruguay issued a sovereign SLB in 2022 that is linked to targets of lowering greenhouse gas emissions and maintaining or increasing native forest area by 4%, relative to a 2012 baseline. It saw significant demand from investors and was four times oversubscribed. n n2. Thematic or ‘use of proceeds’ bonds n nThese differ from SLBs as their performance is not linked to nature-related targets, but rather their proceeds are reserved for nature projects. Clearer guidance and aggregation platforms would improve outcomes for investors. n nIn 2023, Ørsted became the world’s first energy company to issue a blue bond. The €100 million bond will see proceeds allocated to investments, including restoring reef habitats and seafloor vegetation. n n3. Sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) n nThis flexible debt links interest rates to nature targets. Standardized metrics, simpler verification and stronger triggers would benefit SLLs and help them to scale. n nRenewable energy company Iberdrola secured the world’s first credit facility explicitly linked to a water footprint goal in 2022. The interest margin is linked to the company’s target to reduce water withdrawals for its power needs by 50% by 2030, as well as to its CDP water score. BBVA was the sole sustainability coordinator and agent bank for this SLL. n n4. Thematic or ‘use of proceeds’ loans n nThese loans are directed towards specific nature-related projects. Capital flows to this kind of solution would be enhanced through improved clarity on taxonomies and aggregation mechanisms. n nIn 2020, Tornator Oyj, a Finnish forest company, secured a €350 million green bank loan from a syndicate of Nordic banks. The proceeds have been allocated to sustainably managed forest assets. n n5. Impact funds n nThese capital pools invest in nature-positive outcomes, often taking higher risk or longer pathways to generate returns. A stronger pipeline of investable projects, improved governance and standardized metrics are needed to scale this kind of solution. n nSilvania, a $500 million global natural capital fund, invests directly in large-scale restoration, sustainable forestry, coastal and marine ecosystems. n n6. Natural asset companies (NACs) n nAs a new class of public or privately listed company, NACs take the full economic value of nature and convert it to financial flows through equity models. They hold significant potential, but need more transactions to create proof-of-concept, price discovery and replicable investment structures. n nThe world’s first NAC was established by an indigenous-led corporation to safeguard heritage and foster sustainable growth. This boreal NAC (transaction details are not public) is located on more than a million acres of native-owned land. Ecosystem services managed by the NAC include climate regulation, fresh water and flood mitigation. n nDiscover n nWhat is the World Economic Forum doing about nature? n nBiodiversity loss and climate change are occurring at unprecedented rates, threatening humanity’s very survival. Nature is in crisis, but there is hope. Investing in nature can not only increase our resilience to socioeconomic and environmental shocks, but it can help societies thrive. n nThere is strong recognition within the Forum that the future must be net-zero and nature-positive. The Nature Action Agenda initiative, within the Centre for Nature and Climate, is an inclusive, multistakeholder movement catalysing economic action to halt biodiversity loss by 2030. n nThe Nature Action Agenda is enabling business and policy action by: n nBuilding a knowledge base to make a compelling economic and business case for safeguarding nature, showcasing solutions and bolstering research through the publication of the New Nature Economy Reports and impactful communications. n nCatalysing leadership for nature-positive transitions through multi-stakeholder communities such as Champions for Nature that takes a leading role in shaping the net-zero, nature-positive agenda on the global stage. n nScaling up solutions in priority socio-economic systems through BiodiverCities by 2030, turning cities into engines of nature-positive development; Financing for Nature, unlocking financial resources through innovative mechanisms such as high-integrity Biodiversity Credits Market; and Sector Transitions to Nature Positive, accelerating sector-specific priority actions to reduce impacts and unlock opportunities. n nSupporting an enabling environment by ensuring implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and mobilizing business voices calling for ambitious policy actions in collaboration with Business for Nature. n n7. Environmental credits n nThese tradeable certificates for verified environmental benefits are used in compliance or voluntary markets. For this solution to scale, integrity principles, unified standards and stronger local community engagement are needed. n nThe UK’s Biodiversity Net Gain scheme is a regulatory requirement for developers that aims to ensure habitats are left in a measurably better state than before development. By law, developers must deliver a net biodiversity gain of 10% – either by creating biodiversity on site, investing in off-site gains, or buying statutory biodiversity credits from the UK government. n n8. Debt-for-nature swaps (DNS) n nIn exchange for conservation or restoration commitments, these mechanisms restructure sovereign debt, often with improved financial terms. Increased standardization, better governance, collaborative platforms, plus an extended pipeline of eligible debt are all required to scale DNS. n nBarbados’s DNS, secured in 2024, was designed to finance water and sewage resilience projects. Structured as a sovereign SLL, it was tied to volume and quality targets from reclaimed water in treatment plants. Failure to meet the targets, critical in a highly water-scarce country, would trigger financial penalties. n n9. Payments for ecosystem services (PES) n nThese contracts reward conservation efforts for specific ecosystem services and are largely driven by the public sector. To engage the private sector, longer-term contracts, aggregation, standardized blueprints and integration with supply chains are all required. n nVEJA’s PES scheme in the Amazon rewards sustainable rubber sourcing. Since 2018, the footwear brand has paid rubber tappers an 80% premium above market rates for deforestation-free wild rubber. By 2021, over 1,000 tonnes had been purchased from 435 suppliers, enabling VEJA to both meet its sustainability goals and build stronger, more resilient supply chains. n n10. Internal nature pricing (INP) n nThis is a novel, voluntary shadow pricing or fee-based tool that’s similar to internal carbon pricing. The aim is to incentivise nature-positive performance in companies or across investment portfolios, but pilots are required to establish their effectiveness as a governance and investment tool. n nThere are no direct examples of this model – it’s so new. There are comparable examples from carbon pricing schemes, however. Take Microsoft’s internal carbon fee, which charges its own business groups a certain amount based on tracked emissions. n nNo ‘perfect’ single solution n nAs the examples above show, success in financing nature isn’t just theory – it’s already happening. But while momentum is building and the market is growing, it is still fragmented. n nPrivate finance for nature reached over $102 billion in 2024, yet nearly $7 trillion still flows annually into nature-negative activities. Global biodiversity finance needs to hit at least $700 billion per year, but public and private flows remain far short of this, while markets are nascent and unstandardized. n nMultistakeholder action is critical to bridging the investment gap and delivering real impact through nature finance. These five enabling actions, outlined in the report, will be essential to driving this transition with the support of the public, private and multilateral sectors: n n2. Strengthen structuring, approaching and de-risking mechanisms