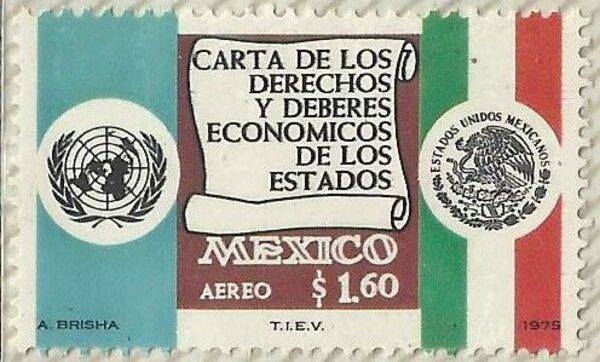

In 1974, during the Cold War, the Global South managed to introduce a document within the UN corridors that aimed to alter the foundations of dominant capitalism: the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States (Resolution 3281). This revolutionary text proclaimed, among other things:

Article 1 (Permanent Sovereignty): Every state has the sovereign and inalienable right to choose its economic, political, social, and cultural system according to its people’s will, without external interference or threats.

Article 2: Every state exercises full sovereignty over its natural resources and economic activities. It can regulate foreign investment, supervise multinational corporations, and, if necessary, expropriate assets with appropriate compensation according to its laws and circumstances.

Article 7: Recognizes the right of states to restructure their debts.

More than half a century later, it is surprising how a manifesto, during the Cold War, openly declared that natural resources belong to the people, that multinational corporations must obey local laws, and that no country is obligated to pay debts incurred by illegitimate governments or that the debt itself was illegitimate.

Today, some of these principles would be labeled as “Trotskyist,” demonstrating the ideological regression and imbalance of the global economic order that the charter sought to counteract. Its goal was clear: to establish a new international economic order based on equity, sovereignty, cooperation, and the common good.

While figures like Kissinger promoted coups in Latin America and Anglo-Saxon oil companies plundered Africa, the charter was condemned to oblivion. The United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom —the current defenders of “global rules”— sabotaged it. By the 1980s, with Reagan and Thatcher at the helm, neoliberalism had captured the IMF and the World Bank, turning them into tools of financial capital. The doctrine was simple: indebt, privatize, deregulate, and subordinate the state to the market.

During the 2008 financial crisis, while most countries bailed out the culprits, Iceland took a different path:

– It did not rescue private banks. It partially nationalized the internal system and allowed insolvent entities to fail.

– It imposed capital controls (2008–2017), preventing capital flight to stabilize its currency.

– It protected the population, ensuring local deposits and avoiding austerity policies.

Additionally, it prosecuted and imprisoned 26 corrupt bankers and subjected the fraudulent debt payment to a referendum. 93% voted NO. The result? From 2010 to 2025, Iceland grew at an annual rate of 3% (compared to 0.5% in the EU), reduced unemployment from 9% to 3%, and public debt fell from 90% to 40% of GDP.

When Greece faced its crisis in 2010 and 2015, it chose a very different path. Despite the “OXI” (NO) referendum, where 61.31% voted against austerity, Tsipras’ government ended up accepting a third memorandum imposed by the Troika (IMF, ECB, EU). The cost was devastating:

– Unemployment reached 27.8% in 2013 (60% among youth), still at 12% in 2025.

– Mass exodus: 500,000 young people emigrated from 2010.

– Forced privatizations: airports, ports, water, and energy.

– Pensions cut by 40%; retirees survive on €500 per month.

– Debt rose from 127% of GDP (2009) to 180% (2018), hovering around 160% in 2025.

– 92% of the “rescues” went to German and French banks.

Some analysts attribute this difference to the fact that Iceland had its own currency. However, beyond the euro, it was a matter of political will and sovereignty.

The Greek crisis (2010-2018) was a laboratory for how neoliberalism imposes illegitimate debts through institutions like the IMF, ECB, and European Commission (the “Troika”). Although the UN did not intervene directly, its legal and technical framework supports the idea that Greece could have repudiated part of its debt.

UNCTAD, in its 2015 report, classified Greek debt as odious, recommending an audit and a 50% haircut. That same year, the UN General Assembly approved principles for restructuring sovereign debts, such as:

1. Transparency and public audit.

2. Prohibition of external interference.

3. Respect for human rights.

Greece could have invoked them but chose not to. As often happens, legal principles were ignored by realpolitik.

Today, the UN seems a shadow of what it aspired to be in 1974. Its resolutions on Palestine are vetoed; its warnings about climate change, ignored. Its vision of economic sovereignty is trampled.

The IMF continues to operate like a mafia debt collector, imposing adjustments that enrich creditors and impoverish peoples. What did the UN do for Greece? Nothing. And the same could be said of Gaza, Yemen, or Ukraine. The UN observes but does not act.

The international system is becoming an anarchic system where there is no night watchman, no superior authority to turn to if a state acts against you. As John J. Mearsheimer, professor of political science at the University of Chicago, says, “if you are weak, there is a serious chance that you will be taken advantage of,” no one wants to appear feeble.

Some, like Sergey Lavrov, propose that the UN Charter be the legal basis for a new multipolar order. An idea that, though questioned for its geopolitical origin, raises a valid point: the “rules-based order” promoted by the West has become a tool to consolidate its hegemony. The idea of “America First” is alarmingly similar to Hitler’s slogan “Germany above all,” and a bet on “peace through strength” could be the coup de grace to diplomacy.

The Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States was not destroyed by neoliberalism alone but also by its accomplices, those who, from power, shelved it for considering it too uncomfortable.

But the document still exists. Dormant, yes. Forgotten, perhaps. But not dead. And in a world where debates on sovereignty, debt, and economic justice are resurfacing, its content regains relevance.

— new from Rebelión