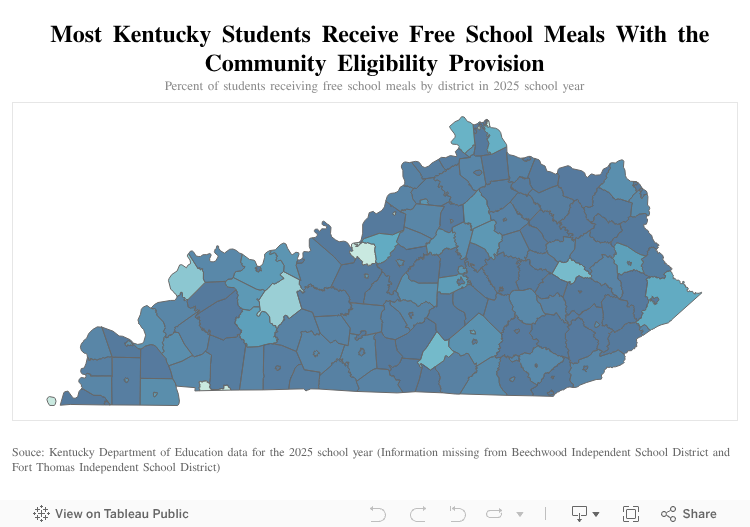

In Kentucky, over 213,830 children faced food insecurity last year—approximately one in five minors experiencing hunger. Poor nutrition has lasting effects on health and economic prospects. To address this, various feeding programs aim to provide meals before, during, and after school, as well as during summer breaks. However, proposed federal reductions under H.R.1, known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), could severely limit the reach of these initiatives. n nThe legislation includes cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid, both of which are linked to eligibility for free school meals. Currently, many students qualify automatically through participation in these programs—a process called direct certification. This method reduces administrative burdens, minimizes errors, and decreases stigma, ensuring more children receive meals. Under OBBBA, families losing SNAP or Medicaid may also lose automatic access to school feeding programs, forcing them to navigate complex application processes that often deter enrollment. n nAs of 2024, 552,673 Kentucky students—82% of the total—were eligible for free or reduced-price breakfast and lunch, according to the Kentucky Department for Education. Nearly 90% of schools offering these meals participate in the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), which allows institutions with high poverty rates to serve all students at no cost without individual applications. In 2024, 527,816 students across 1,162 schools benefited from CEP. This widespread adoption helped Kentucky avoid the steep declines in meal participation seen elsewhere after pandemic-era support ended. n nOnce OBBBA is fully implemented, hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians could lose Medicaid due to new work reporting mandates, and at least 50,000 may lose SNAP entirely. This would affect CEP eligibility in two ways: first, by removing automatic qualification for students whose families lose benefits; second, by disqualifying some schools from CEP due to lower concentrations of low-income students, potentially forcing them to charge for meals. n nAfter-school and summer feeding programs are also at risk. The Child and Adult Care Feeding Program (CACFP) supports nearly 450 sites with meals and snacks. The Seamless Summer Option served 6,184 children across 23 districts, while the Summer Food Service Program reached another 2,250 locations. The Summer EBT program provided nearly $45 million in grocery assistance to around 400,000 children. Reduced SNAP and Medicaid participation could shrink funding and participation in these programs, limiting support for vulnerable families. n nAdditionally, families receiving aid through the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program may face new hurdles. Some qualify for WIC based on SNAP or Medicaid enrollment, which serves as proof of income eligibility—eliminating the need for additional documentation. Losing those benefits would require families to submit extra paperwork, increasing the risk of disenrollment. n nWell-funded school meal programs improve academic performance and health. Students with consistent access to meals achieve higher test scores, attend school more regularly, and experience better physical and mental health outcomes. With federal support shrinking, state-level investment is more critical than ever. The Kentucky General Assembly could mitigate the impact by increasing funding for CEP, expanding the School Breakfast Program, or supporting CACFP for childcare providers. n nFor many children, school meals represent the most nutritious—and sometimes the only—food they receive each week. Protecting these programs is essential to ensuring student success and long-term well-being. n

— news from Kentucky Center for Economic Policy

— News Original —

Recent Federal Cuts Could Increase Student Hunger

Last year, 213,830 Kentucky kids didn’t get enough to eat. That’s roughly one in five of children going hungry. Inadequate nutrition has lifelong consequences for health and economic wellbeing. To combat this harm, multiple feeding programs try to keep Kentucky kids fed before, during and after school, and when school is out in the summer. But by cutting health and food assistance, H.R.1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), will result in these programs reaching fewer students. n nOBBBA cuts the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which can cause kids to lose access to food at home. And cuts to SNAP and Medicaid in OBBBA can then cause the loss of meals at school as well. Currently, many children automatically qualify for free school meals based on their participation in these programs. This direct certification allows these programs to reach eligible families without having to process individual applications, resulting in reduced administrative costs, less stigma, fewer potential for errors and more qualifying students. But with the passage of OBBBA, Kentuckians that lose their SNAP and Medicaid could also lose access to child feeding programs. Many will be required to fill out additional paperwork, which has been shown to reduce the likelihood that people successfully qualify for programs like these. Action will be needed by the Kentucky General Assembly this coming session to ensure schools can continue to provide the most basic school supply — food. n nFederal cuts jeopardize free school meals n nIn Kentucky, 552,673 students (82%) qualified for free or reduced school breakfast and lunch as of 2024, according to Kentucky Department for Education data. Nearly 90% of schools with free and reduced meals feed their students by participating in the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), which allows schools and districts to provide meals at no cost to all students without filling out individual applications. In addition to reducing paperwork, CEP lowers costs for schools and eliminates stigma for kids who get free meals. In 2024, 527,816 students in 1,162 schools qualified for CEP to provide meals at no cost. Kentucky’s high CEP participation rate allowed us to avoid the major drops in school meal participation many states saw after the end of pandemic-era supports. n nOnce the OBBBA is fully implemented, hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians are expected to lose Medicaid due to new work reporting requirements and at least 50,000 Kentuckians will be newly at risk of losing SNAP entirely. This reduction in SNAP and Medicaid participation will impact Kentucky’s CEP rates in two ways. First, students could lose direct certification through the loss of Medicaid and SNAP, requiring their parents or caregivers to complete an application for free meals. This added hurdle will inevitably trip up some families. Second, as people lose SNAP and Medicaid some schools currently providing free meals for all students through the CEP program will no longer qualify for the program, forcing them to begin charging some students for meals. In CEP, the higher the concentration of students with low incomes, the higher the much-needed federal reimbursement dollars the school receives, some qualifying schools may not be able to afford to participate. n nSummer and after-school meals are also at risk now n nSNAP and Medicaid participation is also used to certify kids for programs that help feed them after school and in the summer, when child hunger is highest. For example: n nThe Child and Adult Care Feeding Program (CACFP) provides almost 450 sponsor sites for child care or afterschool programs with meals and snacks. n nThe Seamless Summer Option fed 6,184 kids enrolled in 23 school districts during the summer. n nThe Summer Food Service Program helped feed school kids at another 2,250 sites. n nThe Summer EBT program provided almost 400,000 kids with over $45 million in grocery money during the summer. n nAll of these programs could see a reduction in participation with fewer children receiving SNAP and Medicaid, reducing the resources available to school districts, child care providers, and the state to offer many of these supports. n nIn addition to school-aged kids losing access to programs with the reduction of SNAP and Medicaid, infants, children under 6 and breastfeeding or postpartum women getting help with groceries through Women, Infants and Children (WIC) could lose benefits. Some families that participate in SNAP and Medicaid are “adjectively eligible” for WIC, meaning their participation in those programs proves they are income-eligible and don’t have to verify their household income. They must still complete an application to show they meet other criteria like nutritional risk but don’t have to face the barrier of proving income eligibility. If a family loses their SNAP or Medicaid, they will have to start submitting additional paperwork to prove their income eligibility for WIC or risk losing that help with groceries. n nStudent nutrition programs are vital, and need state investment n nAdequately funded school meals make it easier for schools to afford healthy food options and improves academic achievement and health outcomes. Students with access to school meals have higher standardized test scores and attend more days of school. Research shows access to school breakfast and lunch improves health, including fewer nurses visits, better nutrition, reduced risk of developing obesity, better food security and improved mental health. n nIt is more important than ever that the Kentucky General Assembly help kids get fed at home and in school. Lawmakers can consider investments in school meals, like additional funding to make participation in CEP more feasible for districts, or through supplementing funding for the School Breakfast Program. Kentucky lawmakers could also supplement CACFP funding for afterschool care and child care centers to ensure decent nutrition for kids outside the school. With federal cuts to SNAP, having enough food just became more difficult. For many Kentucky kids, meals at school are often the most nutritious, and sometimes the only, food they will eat each week. Kentucky legislators should protect that key ingredient to student success.