The informal or shadow economy remains a persistent challenge in developing countries, affecting tax revenues, distorting labor markets, and undermining institutional effectiveness. According to the International Labor Organization, around 60% of the global workforce aged 15 and older—approximately 2 billion people—are engaged in informal economic activities, predominantly in emerging economies. This widespread participation reduces government capacity to fund public services and distorts competition, resource allocation, and environmental standards.

However, financial inclusion (FINI) may serve as a counterbalance. By expanding access to formal banking, credit, and insurance, FINI enables individuals and businesses to transition from informal operations to regulated financial systems. This shift can enhance savings, investment, and entrepreneurial activity, thereby boosting productivity and economic stability. Research indicates that improved access to financial services reduces incentives for tax evasion and informal operations, particularly where formal institutions offer reliable and accessible alternatives.

This study analyzes data from 120 developing nations between 2002 and 2020 to assess whether financial inclusion moderates the negative impact of the shadow economy on economic growth (ECOG). Using both the MIMIC and DGE models to estimate informal sector size, and applying difference and system GMM estimators to address endogeneity, the research finds that stronger financial systems—measured through financial market development (FMD) and financial institution development (FID)—help reduce the detrimental effects of informal economic activity.

Control variables such as physical capital (measured by gross fixed capital formation), human capital (via secondary school enrollment), industrialization (industry value added as a share of GDP), and inflation (GDP deflator) were included to isolate the core relationship. The findings suggest that while the shadow economy generally hampers growth—especially in countries with weak institutions—higher levels of financial inclusion weaken this negative correlation.

Theoretical perspectives vary: some argue the informal sector “sands the wheels” of growth by undermining governance, while others suggest it “greases the wheels” by absorbing unemployment and stimulating grassroots entrepreneurship. Yet empirical evidence increasingly supports the view that unchecked informality impedes sustainable development. Studies across African, Asian, and Latin American economies confirm that greater financial access correlates with reduced informal activity.

Policies promoting affordable and inclusive financial services could therefore play a pivotal role in formalizing economic activity. When individuals and small enterprises can access credit, save securely, and participate in regulated markets, they are less likely to rely on off-the-books transactions. This transition not only strengthens macroeconomic stability but also enhances long-term growth potential.

The research contributes to policy discourse by demonstrating that financial development is not merely a growth accelerator but also a tool for reducing economic informality. By integrating financial inclusion strategies into broader economic reforms, developing nations may create self-reinforcing cycles of formalization, investment, and inclusive development.

— news from Springer Nature

— News Original —

Shadow economy, financial inclusion and economic growth Nexus: evidence from developing countries

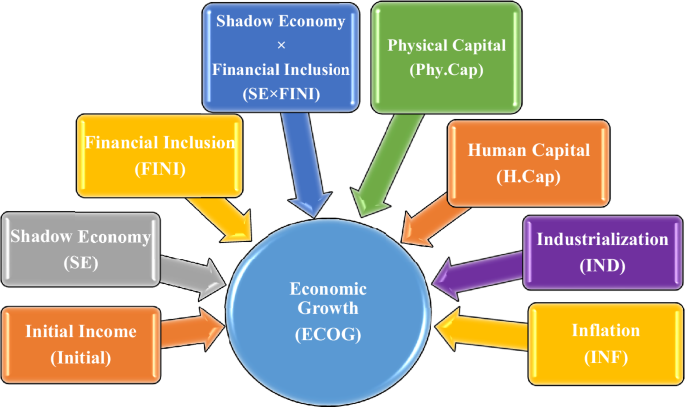

Shadow economy (SE) is a global economic issue, especially creating challenges for policymakers in developing countries (Ahmad and Hussain, 2023). It operates outside formal regulations and tax systems, which leads to significant revenue losses and complicates economic planning and policy implementation. Its informal nature distorts labor market statistics and economic indicators (Gharleghi and Jahanshahi, 2020). According to estimates of the International Labor Organization, approximately 2 billion people, making up 60% of the world workforce aged 15 and older, are now engaged in different levels of the SE activities, most of which are in developing countries (ILO, 2018). A large SE decreases tax revenue, which reduces the capacity of the government to fund for the publicly provided goods and services, and weakens economic and social institutions, causes distortions in market competition, inefficient utilization of resources in the production process, and leads to a decline in the country’s overall production capacity (Schneider and Enste, 2000; Baklouti and Boujelbene, 2020). It hurts the financial development process by increasing financial destruction due to tax evasion (Elgin and Uras, 2013). It spreads low-return technology and causes environmental pollution (Blackburn et al. 2012; Ahmad and Hussain, 2024). The above-mentioned negative consequences of the SE collectively hurt overall economic performance. n nFinancial sector development is key to boosting economic growth (ECOG) (Younas et al. 2022). Financial inclusion (FINI) is instrumental in stimulating ECOG by making lending to businesses easier, mobilizing savings, encouraging entrepreneurship and innovation, efficiently allocating resources, improving capital formation, enhancing productivity, attracting investment, and fostering stability and inclusivity within the economy (Shahbaz et al. 2022). FINI also plays an important role in restricting the growth of the SE. FINI can facilitate individuals and businesses by improving informal sector access to formal financial services, including banking, credit, and insurance. This can allow them to save, invest, and protect their money, resulting in enhanced economic opportunity in the formal economy and reduced SE opportunities (Capasso and Jappelli, 2013; Berdiev and Saunoris, 2016). Services offered by official financial markets and financial institutions in countries with a developed financial sector are better than incentives for tax evasion; hence, business enterprises have no incentives to engage in informal sector activities (Haruna, 2023). n nDespite extensive empirical and policy discussions on SE, a deeper understanding of how countries can effectively contain its adverse effects on ECOG is still lacking. This is especially important for developing countries where informal activities are widespread and structurally embedded due to weak financial systems, poor regulatory enforcement, and limited institutional capacity. The central motivation of this study stems from this persistent structural challenge: How can developing economies reduce their dependence on the informal sector and improve formal sector productivity? In the face of weak tax enforcement and limited state capacity, strengthening financial systems may offer a viable solution. Specifically, we explore whether FINI, as reflected by both financial market development (FMD) and financial institution development (FID), can function as a mechanism that weakens the negative economic consequences of the SE. This motivation is grounded in a broader policy concern. In the absence of financial access and credible formal alternatives, individuals and businesses may have no incentive to operate within the legal framework of the economy. This calls for an empirical evaluation of how improving FINI could create disincentives for informality and stimulate growth. n nAlthough the literature has extensively studied the individual impacts of the SE and FINI on ECOG (Pradhan et al. 2019; Sharma and Kautish, 2020; Baklouti and Boujelbene, 2020; Younas et al. 2022), it does not address the interactive relationship between these variables. This constitutes a crucial gap, because without understanding the interaction, we cannot determine whether financial development policies offset the damage caused by informality. Moreover, theoretical justifications exist for such a moderating relationship: formal financial systems reduce credit costs, improve investment efficiency, and create incentives for informal enterprises to formalize (Bose et al. 2012; Blackburn et al. 2012). However, empirical validation of this interactive channel is virtually absent in the current literature. Our study addresses this deficiency by analyzing the interactive term (SE × FINI) in a dynamic panel setting, thereby identifying whether increasing FINI can systematically reduce the marginal harm of shadow activities on economic performance. n nThis study provides several novel contributions to the literature and policy discourse. First, we are among the first to examine the moderating role of FINI in the relationship between the SE and ECOG using a large panel of 120 developing countries over the period 2002–2020. This is critical because it shifts the focus from analyzing standalone effects to exploring interaction effects, which are more relevant for designing targeted financial and regulatory interventions. Second, by decomposing FINI into FMD and FID, we present a two-dimensional framework that captures the structural and functional elements of financial systems. This allows for a more comprehensive and policy-relevant interpretation of FINI. Third, we address potential endogeneity and dynamic bias by applying difference GMM and system GMM estimators, ensuring credible causal inference. Fourth, we enhance robustness by using two distinct proxies for the SE (MIMIC and DGE models), thereby validating our findings across alternative measurement strategies. Taken together, these contributions help establish a new line of inquiry into how financial architecture can be used to promote growth and dismantle informal economic structures, which is vital for long-term development. n nFinally, the main aim of this study is to investigate the effect of the SE on ECOG in developing countries and the role of FINI in moderating this relationship. Specifically, we hypothesize that: n nHypothesis 1 (Null Hypothesis): The SE has no relationship with ECOG in developing countries. n nHypothesis 2 (Null Hypothesis): FINI has no relationship with ECOG in developing countries. n nHypothesis 3 (Null Hypothesis): FINI does not moderate the negative impact of the SE on ECOG in developing countries. n nThe rest of the study is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the theoretical underpinnings of the research. Section 3 provides a detailed review of relevant literature. Section 4 describes the materials and methods used in the analysis. Section 5 presents the empirical results. Section 6 offers a comprehensive discussion of the findings along with policy implications. Finally, Section 7 concludes the study by highlighting key research limitations and proposing directions for future research. n nThe nexus between the SE and ECOG in developing economies has been the subject of critical academic inquiry. Several theories exist to explain the complex relationship between these two variables. One of the most prominent is Institutional Theory, which attributes the growth of the SE to weak institutions, corruption, and ineffective governance (La Porta and Shleifer, 2014). However, the literature suggests that the effect of the SE on ECOG is not universally negative. To this end, two prominent theories explain the relationship between the SE and ECOG: the Sands the Wheels Hypothesis and the Greases the Wheels Hypothesis. n nSands the Wheels Hypothesis posits that the SE significantly hampers ECOG by distorting markets, reducing tax revenues, and fostering inefficiency (Hoinaru et al. 2020). The SE “sands the wheels” of economic activity by reducing the availability of resources for public goods and services, undermining government policies, and increasing informal labor market practices that distort fair competition (Schneider, 2005). A large SE is often linked to poor governance, ineffective regulations, and increased corruption, which hinder sustainable development and ECOG. Conversely, the Greases the Wheels Hypothesis suggests that the SE may positively influence ECOG, particularly in developing economies where formal economic structures are weak (Hugo et al. 2021). Informal sector activities can provide vital job opportunities and foster entrepreneurship, especially where formal sector jobs are scarce. Informal activities can “grease the wheels” of ECOG by absorbing excess demand, providing labor to sectors that might otherwise be underserved, and facilitating innovation that strengthens the overall economy (Schneider, 2011). In this view, the SE can serve as a safety net, supporting individuals and businesses excluded from formal economic systems (Loayza, 1996). n nThese two contrasting perspectives highlight the complex nature of the SE’s impact on ECOG. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for designing effective policies that promote formalization and improve governance, particularly relevant in developing economies where FINI plays a key role. Meanwhile, FINI has become a primary engine of formal economic development in developing countries. FINI, which includes access to formal financial services such as financial banking, credit, and insurance, can aid the transition from informal to formal sector (Demirguç-Kunt and Klapper, 2012). Access to credit and savings brings FINI, which promotes entrepreneurship, innovation, and stimulates economic productivity (Beck et al. 2000; Henderson et al. 2013). Younas et al. (2022) demonstrate that FINI significantly impacts ECOG in developing countries, as it allows businesses to formalize that might otherwise operate informally. In FINI, financial services that are more attractive than the informal ones will reduce the size of the SE. n nThe theoretical framework for this study is also based on the finance-growth nexus theory, which holds that FINI promotes ECOG by increasing investment and productivity (King and Levine, 1993). The interplay between FINI and the SE is critical: The adverse effects of the SE on the ECOG decrease as FINI increases. This reduces the harmful effects of SE through the general development of financial markets and institutions so as to provide an alternative to offering formal financial solutions to pull businesses away from informal activities (Sharma and Kautish, 2020). n nWe incorporate several control variables to account for key determinants of ECOG, including physical capital (Phy.Cap), human capital (H.Cap), industrialization (IND), and inflation (INF). Investment in infrastructure and productive capacity (Phy.Cap) is a spectacular driver of ECOG (Barro, 2003). In enhancing innovation and productivity, H.Cap is a significant factor in sustainable economic development (Barro, 1991). IND is the key for changing the economies from agro to industrial and service-based economic systems, improving productivity and ECOG (Opoku and Yan, 2018). Then, it acts as the proxy for macroeconomic stability, where high inflation is most likely to go along with economic volatility and uncertainty, leading to a lack of investment and hindrance to ECOG (Barro, 2013). n nBased on this theoretical framework, this study posits that FINI has an intervening role in the relationship between the SE and ECOG through formalization and access to capital that supports growth. The above-mentioned control variables are included to give a complete understanding of the various factors that play a role in determining economic performance in developing countries. This study contributes to analyzing factors that promote the economy’s growth, considering the adverse effects of the SE by incorporating both FINI and critical control variables. It illuminates the necessity for policies that stop the SE from growing and increase people’s access to finance, so that economic growth is inclusive and robust (Allen et al. 2016). The model describing the interconnectedness among these factors is specified in the equation below: n n$${{ rm{ECOG}}}_{{ rm{it}}}={ rm{f}} left({{ rm{Initial}}}_{{ rm{it}}},{{ rm{SE}}}_{{ rm{it}}},{{ rm{FINI}}}_{{ rm{it}}},{ rm{SE}} times {{ rm{FINI}}}_{{ rm{it}}},{{ rm{Phy}}.{ rm{Cap}}}_{{ rm{it}}},{{ rm{H}}.{ rm{Cap}}}_{{ rm{it}}},{{ rm{IND}}}_{{ rm{it}}},{{ rm{INF}}}_{{ rm{it}}} right)$$ n n(1) n nInitial represents the initial income, and SE × FINI reflects the interaction between the SE and FINI. Figure 1 presents the theoretical framework. n nShadow economy and economic growth n nThe current literature has undertaken numerous empirical and theoretical examinations to explore the association between the SE and ECOG. However, no definitive conclusions have emerged from these studies. Schneider and Enste (2000) highlighted the complexity of the SE’s impact on growth. While SE activities often lead to inefficient resource allocation, the income they generate is largely reinvested in the formal economy, which can stimulate growth. Similarly, Schneider (2011) found that the influence of the SE on ECOG differs between developed and developing economies. In developed economies, the SE positively and significantly influences ECOG, as it generates additional income that stimulates consumption within the official economy. However, massive tax evasion in developing economies hinders ECOG because of a lesser provision of essential publicly provided goods and services. n nIn addition, Baklouti and Boujelbene (2019) demonstrate that if the participation in the unofficial sector grows, the tax base decreases, damaging public infrastructure investment and rendering public services less efficient. These factors can seriously inhibit a country’s ECOG. In 33 developed economies and 17 developing economies, Baklouti and Boujelbene (2020) examined this relationship. Their results suggested that the relationship is bidirectional in developed economies, but in developing economies, the relationship is unidirectional and negative. Younas et al. (2022) also found that SE has decreased the level of ECOG in developing economies. Esaku (2021) further investigates the link between the two in Uganda. His finding shows that an expansion of the unofficial sector significantly hampers the growth rates over the short and long run. Likewise, Elgin and Birinci (2016) conducted a comprehensive analysis of 161 economies and revealed a nonlinear relationship between these two variables. Consequently, their findings indicate that countries with either a small or large SE tend to have hindered ECOG rates, primarily due to their governments’ incapacity to establish the needed infrastructure that facilitates growth. Similarly, Elgin and Oztunali (2014) examined 141 economies and found that institutional quality also plays a role in the SE and ECOG nexus. For countries with low institutional quality, the relationship between the two is positive. Conversely, for countries with high institutional quality, this relationship becomes negative. n nSome studies present an alternative perspective. In this vein, Wu and Schneider (2019) argue that the income derived from the SE is promptly reinvested within the official economy, thereby positively contributing to ECOG. Williams (2007) also argued that the SE enhances the ECOG because it efficiently absorbs excess demand and supply from the official economic sector and offers employment opportunities for the unemployed labor force. In the same manner, Goel et al. (2019) conducted a study in the United States across a span of one hundred years, and found that, leading up to the Second World War, a negative correlation exists between the SE and ECOG. However, after the war, the relationship became positive. In a micro-level study, Mugoda et al. (2020) found that an increase in the SE can affect ECOG, provided that the SE raises productivity levels that flow over to the formal economy. Although informal businesses are typically less productive, have restricted capital, and employ a significant portion of unskilled labor, they remain vital in creating jobs and generating income for society’s most impoverished and vulnerable individuals (Buehn and Schneider, 2012). The current body of literature generally presents an ambiguous connection between the SE and ECOG. n nFinancial inclusion and economic growth n nThe literature suggests that the progress of financial systems impacts decisions related to saving and investing. It also determines how financial resources are distributed to maximize productivity and offers entrepreneurs the essential credit they need to fund and implement innovative production methods. The literature has emphasized the significant role that FINI plays in accelerating ECOG. Henderson et al. (2013) conducted a study encompassing 101 countries to explore this. Their findings revealed that FINI enhances the ECOG. Furthermore, Chortareas et al. (2015) found similar outcomes when examining this relationship in 37 developed and developing countries. Moreover, Beck et al. (2000) indicated that FINI significantly contributes to ECOG by boosting the savings rate and physical capital growth. Sharma and Kautish (2020) focused on four South Asian middle-income economies and found that FMD and the banking industry are key factors behind the high ECOG in the region. More recently, Younas et al. (2022) revealed that FINI significantly increases the level of ECOG in developing countries. n nFurthermore, Asteriou and Spanos (2019) explored the linkages between two in European Union countries, particularly in light of the repercussions of a recent financial crisis. Their findings indicated that FINI had a positive impact before a crisis; after the crisis, it contributed to a decline in ECOG. Athari (2022) found that greater FINI and reduced political instability significantly enhance banking sector stability across 105 countries. Regional effects are most potent in South and East Asia for inclusion and in high-income OECD nations for political stability. Kirikkaleli and Athari (2020) examined the causal relationship between bank credit supply and ECOG in Turkey, revealing that the linkage varies by bank ownership type and period. Athari et al. (2021) explored the dynamic causal relationship between sectoral credit and ECOG in Australia, revealing that the direction of causality varies by sector. Key findings show that agriculture is credit-driven by growth, while manufacturing credit drives growth, with a positive correlation in the service sector. Numerous other studies have also supported the notion that the progress of the FINI plays a significant role in ECOG, with empirical evidence to support these findings. For example, Pradhan et al. (2019) exposed this relationship in G-20 nations. Similarly, Ehigiamusoe and Lean (2018) researched 16 West African countries and found similar results. A nonlinear relationship is also detected in the literature. In this manner, Samargandi et al. (2015) indicated that advanced financial sectors boost growth in 52 developing economies, but only up to a specific threshold level. Beyond this point, increased finances lead to a lower ECOG. n nFinancial inclusion and shadow economy n nFINI is pivotal in shaping the economies’ formal and informal sectors worldwide. We focus on how FINI influences the dynamics of the SE. To explore this relationship, Haruna (2023) conducted a study in 42 African economies and examined the finance-informal sector nexus using three financial sector proxies, including financial access, financial depth, and financial efficiency. The findings revealed that all three proxies diminish the SE in African economies. In addition, Bose et al. (2012) showed that FINI has a negative relationship with the SE. Just as Ajide (2021) showed, the SE is lower as the level of FINI increases in African countries. Financial development initiatives typically aspire to endorse FINI, indicating that providing cheap and accessible financial services to underserved populations. FINI can bring the businesses in the SE sector into the formal financial system by extending formal financial services to them. This can lead to their own economic opportunities, banking, and investment, and it can help the ECOG in opposition to SE. n nSimilarly, Khan et al. (2023) found that FINI has a more substantial mitigating effect on the size of an SE in non-OIC countries than in OIC countries. Athari et al. (2024) found that lower country risk ratings promote shadow banking growth globally, with varying effects across advanced and emerging economies. It confirms the roles of regulatory arbitrage and macro-institutional factors, offering key insights for policymakers and regulators. Gharleghi and Jahanshahi (2020), based on data from 29 developing and developed economies, have confirmed that the countries with more FINI have smaller SEs than countries with less FINI. Similarly, Berdiev and Saunoris (2016) have found that FINI harms SE size in 161 countries worldwide. n nData and variables n nTo estimate the abovementioned models, we utilize a balanced panel dataset of 120 countries worldwide, from 2002 to 2020. The selection of time and countries is based on data availability. n nEconomic Growth (ECOG) n nECOG serves as a dependent variable. Consistent with prior studies, we measure it as the “log difference of real per capita GDP multiplied by 100.” The measurement of per capita GDP is based on prices from 2015. n nShadow Economy (SE) n nThe models use the SE as a core independent variable. SE is defined here as the hidden production of goods and services that occurs outside the official regulation by public authorities for reasons of money, regulation, or institutional. Monetary motives include tax evasion and social security exclusion; regulatory motives include avoiding bureaucracy or onerous regulations; institutional motives include bribery, closely related to weak political institutions and a poor rule of law (Elgin et al. 2021). We utilize two estimates of SE. 1) The MIMIC Model (Multiple Indicators and Multiple Causes) is based on the premise that the SE is determined by several latent factors that can be inferred from observed indicators, such as tax and unemployment rates. The MIMIC model is widely used in the literature due to its ability to account for the unobserved nature of the SE while considering multiple causes of informality, such as regulatory burden and institutional quality. 2) The DGE Model (Dynamic General Equilibrium Model) uses a dynamic generalization of the MIMIC model that incorporates both observed and unobserved heterogeneity, offering an alternative and complementary perspective on SE activities. The DGE model effectively captures cross-country variations in the informal sector, which may be influenced by a range of country-specific factors, such as governance and economic structure. The MIMIC and DGE approaches were chosen for their robustness and ability to address several challenges in SE measurement, such as endogeneity, data gaps, and measurement errors. These methods have been widely used in similar studies due to their validity and ability to deal with unobserved factors that affect the SE. Furthermore, both models have extensive datasets available for nearly all developing countries, allowing for a comprehensive analysis across a diverse range of economies, making them particularly suitable for global studies involving developing nations. n nFinancial Inclusion (FINI) n nFINI acts as a moderating variable in the models. In this study, the FMD and FID are employed as indicators for FINI. The values of the FMD and FID index range from 0 to 1, where a greater value specifies greater financial market and institution development. We multiplied the financial market index and financial institution index data by 100 to standardize the measurement scale with the variable SE. n nControl variables n nWe incorporate multiple control variables. The “log of the initial GDP per capita” is a proxy for initial income (Initial). Including this variable in our growth model adds a dynamic element and allows us to examine whether there is any convergence or divergence in the growth process among the countries in our sample. Physical capital (Phy.Cap) is measured by “gross fixed capital formation as % of GDP”. Human capital (H.Cap) is measured by “gross secondary school enrollment in percentage”. Both physical and human capital are essential to all growth models (Barro, 2003). Industrialization (IND) is measured by the “value added in industry, including construction, as % of GDP”. Here, value added is a measure that captures the additional economic worth created by industries through their production processes. The inflation (INF) is measured by the “GDP deflator as an annual percentage”. The description of variables is also presented in Table 1. n nModel specifications n nWe propose a model based on the above arguments and previous studies. Moreover, to enhance the accuracy of the models and minimize the risk of overlooking crucial variables, we incorporate several control variables as Barro (2003) recommended. First, we examine the effect of the SE on ECOG. To start the exercise, we develop the model as follows: n n$${log Y}_{{it}}={ alpha log Y}_{{it}-1}+{ beta }_{1}S{E}_{{it}}+ beta {{^ prime}} Z_{{it}}+{v}_{i}+{ omega }_{t}+{ mu }_{{it}}$$ n n(2) n nWhere subscripts i and t denote the country and time period, respectively. vi and ωt are the country and time-specific effects, respectively. μit is the usual error term, and α and β are the respective coefficients. logY represents the log of real per capita GDP. SE is the shadow economy. Z is the vector of control variables, such as physical capital (Phy.Cap), human capital (H.Cap), industrialization (IND), and inflation (INF). n nWe follow the study of Dollar and Kraay (2003) to formulate the more conventional model in which growth acts as a dependent variable that regresses on initial income, the SE, and a set of control variables. Subtracting lagged income from both sides of Eq. (2), we can express it in an alternative form as follows: n n$$ begin{array}{l}{log Y}_{{it}}-{log Y}_{{it}-1} ,={ alpha log Y}_{{it}-1}-{log Y}_{{it}-1} quad qquad qquad qquad , , ,+ ,{ beta }_{1}S{E}_{{it}}+{ beta^{ prime} Z}_{{it}}+{v}_{i}+{ omega }_{t}+{ mu }_{{it}} end{array}$$ n n(3) n nOr n n$${log Y}_{{it}}-{log Y}_{{it}-1} ,= left( alpha -1 right){ mathrm{log}}{Y}_{{it}-1}+{ beta }_{1}S{E}_{{it}}+{ beta^{ prime}Z}_{{it}}+{v}_{i}+{ omega }_{t}+{ mu }_{{it}}$$ n n(4) n nOr n n$${{ECOG}}_{{it}}={ beta }_{0}{{Initial}}_{{it}} ,+{ beta }_{1}S{E}_{{it}}+{ beta ^{ prime}Z}_{{it}}+{v}_{i}+{ omega }_{t}+{ mu }_{{it}}$$ n n(5) n nWhere ({{ rm{ECOG}}}_{{ rm{it}}}= ,{ log { rm{Y}}}_{{ rm{it}}}-{ log { rm{Y}}}_{{ rm{it}}-1} ) represents ECOG, ({{ rm{ beta }}}_{0}={ rm{ alpha }}-1 ) is the convergence coefficient, and ({{ rm{Initial}}}_{{ rm{it}}}= log {{ rm{Y}}}_{{ rm{it}}-1} ) is the initial income use to check the convergence in the growth process. Equation (5) is the final model to be estimated to examine the impact of the SE on ECOG. n nTo explore the moderating role of FINI in the nexus between the SE and ECOG, we reformulate Eq. (5) as follows: n n$${{ECOG}}_{{it}}={ beta }_{0}{{Initial}}_{{it}} ,+{ beta }_{1}S{E}_{{it}}+{ beta }_{2}{{FINI}}_{{it}}+{ beta }_{3} ,(S{E}_{{it}} times {{FINI}}_{{it}})+{ beta ^{ prime}Z}_{{it}}+{v}_{i}+{ omega }_{t}+{ mu }_{{it}}