Economic uncertainty, driven by global market instability and external shocks such as pandemics and geopolitical tensions, continues to challenge individuals and societies worldwide. Its ripple effects are evident across key socioeconomic indicators including suicide rates, unemployment, economic growth, and trade openness, all of which influence national and individual well-being. Understanding the drivers of economic uncertainty is essential, particularly in light of recent global disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to widespread lockdowns, supply chain breakdowns, and record-high economic policy uncertainty indexes (Gopinath, 2020; Ahir et al. 2023). During 2020, global GDP contracted by 3%, marking the worst decline since the 1930s Great Depression (Gourinchas, 2024), while global trade dropped by 8% due to disrupted logistics and weakened demand. Unemployment peaked at 6.6% globally that year, with youth joblessness significantly exceeding adult levels (United Nations, 2023). Additionally, financial distress during the pandemic contributed to rising suicide rates in several nations (Er et al. 2023).

Scholarly interest in the interplay between economic uncertainty and socioeconomic outcomes has grown. Research indicates that lagged economic instability, along with fluctuations in employment and growth, may elevate suicide risks (Claveria, 2022a). In countries like France, Italy, and Spain, youth employment has proven more sensitive to shocks in economic policy uncertainty than adult employment (Dajčman et al. 2023), highlighting the need for targeted labor policies. Investigating suicide trends can uncover deeper societal challenges such as poverty, inequality, and inadequate mental health infrastructure. While mental health awareness has improved in recent years (Brådvik, 2018; Tao and Cheng, 2023), low-income nations often deprioritize psychological care due to competing socioeconomic demands, limiting policy responses.

Regional conflicts, such as the war in Ukraine, have further destabilized economies by disrupting energy markets and inflating prices of essential goods. National economic health is commonly assessed through GDP and employment metrics, with established research showing an inverse relationship between economic expansion and joblessness (Claveria, 2022a). In today’s interconnected world, international trade remains vital. Some nations rely heavily on exporting commodities like food and electronics, while others depend on imports but export high-value goods such as integrated circuits, petroleum, vehicles, and gold (Anwar et al. 2024). Analyzing trade dynamics and investment in infrastructure helps assess how commerce shapes global economic resilience.

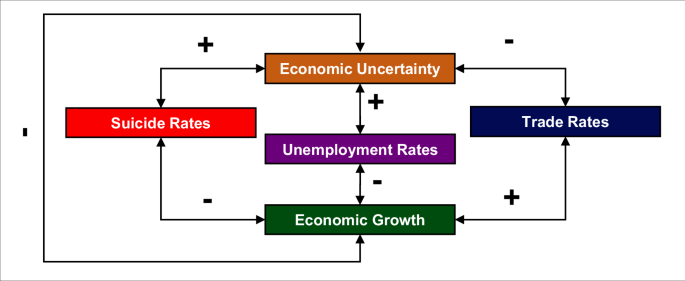

This study investigates the causal and long-term relationships between economic uncertainty and four socioeconomic variables—suicide rates, unemployment, economic growth, and trade openness—across 30 high-uncertainty countries over 23 years. It uses the World Uncertainty Index (WUI) to identify nations most affected. Unlike prior research that often examines one or two variables in isolation, this analysis incorporates five dimensions and applies Granger Causality and Cointegration Tests to explore bidirectional influences. The methodology enables policymakers to design interventions aligned with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, including targets related to health (SDG 3), education (SDG 4), decent work (SDG 8), innovation (SDG 9), reduced inequality (SDG 10), and global partnerships (SDG 17).

Theoretical frameworks such as Durkheim’s social integration theory suggest that economic instability weakens communal bonds, increasing vulnerability to suicide. Job search theory posits that uncertainty makes unemployed individuals hesitant to accept new roles, while real options theory explains why firms delay hiring and investment during volatile periods, contributing to higher joblessness. Keynesian economics argues that uncertainty reduces consumer and business spending, slowing economic activity (Keynes, 1936), and prospect theory highlights how individuals weigh risks differently under stress (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). Endogenous growth theory further suggests that uncertainty discourages innovation, undermining long-term economic stability (Romer, 1986).

Regarding trade, transaction cost theory indicates that uncertainty raises the costs of international commerce, pushing firms toward domestic markets (Coase, 1937). Trade Policy Uncertainty (TPU) theory suggests that unpredictable regulations deter cross-border investment (Handley, 2014), while the gravity model helps predict bilateral trade flows based on economic size.

Data was drawn from public global databases, covering 690 observations across 30 countries. Missing values were estimated using regression or averaging techniques. The WUI, derived from Economist Intelligence Unit reports, measures uncertainty by analyzing the frequency of the term “uncertainty” in country forecasts, normalized by document length. While the index offers broad coverage and quarterly updates, it may reflect reporting biases and aggregates diverse uncertainty types.

Methodologically, the study employed Granger Causality and Cointegration Tests to assess short- and long-term relationships. The Augmented Dickey-Fuller test confirmed variable stationarity, and lag length was selected using the Moment Akaike Information Criterion (MAIC). Stability of the Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model was verified through eigenvalue analysis within the unit circle. The Westerlund cointegration test accounted for structural breaks, such as economic crises, enhancing robustness.

Findings contribute to both academic and policy domains by offering a comprehensive, multi-variable analysis of uncertainty’s socioeconomic impacts. Visualizations and statistical tools, including STATA, Jupyter Notebook, and Excel, supported data interpretation. The results aim to inform evidence-based strategies that enhance resilience in high-uncertainty environments.

— news from Springer Nature

— News Original —

Economic uncertainty: a worldwide concern, a causal and cointegrating analysis among high uncertainty countries

The economic uncertainty which is driven by global market instability and external shock, particularly pandemics and geopolitical conflicts, pose significant challenges affecting individuals and societies. The effects of uncertainty echo through socio-economic domain, especially in suicide rates, unemployment, economic growth and trade openness, which shape individual and country level prosperity. Understanding the key factors driving economic uncertainty is crucial, especially given the complexities introduced by recent global developments, especially the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had detrimental effects caused by lockdowns, supply chain disruptions with high economic policy uncertainty indexes being at an all-time high (Gopinath, 2020; Ahir et al. 2023). In context of the study’s variables, during this period global growth fell to −3% in 2020, which is considered the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s (Gourinchas, 2024), with the global trade contracting by 8% in 2020 due to supply chain disruptions and reduced demand for goods. During the COVID-19 period the global unemployment rates peaked at 6.6% in 2020, with youth unemployment remaining significantly higher than adult rates (United Nations, 2023). There is a visible increase in suicide rates with some countries reporting higher rates due to financial hardships during the pandemic period (Er et al. 2023). n nThe relationship between economic uncertainty and socioeconomic variables has garnered significant scholarly attention in the recent years. When exploring economies, there is an increase in lagged economic uncertainty, as well as in unemployment and economic growth, may lead to an increased risk of suicide (Claveria, 2022a). Youth unemployment is more susceptible to Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) shocks than adult unemployment in France, Italy, and Spain (Dajčman et al. 2023). These imply a heavy urge among researchers to explore the interplay of economic uncertainty and its counterparts in the modern world. n nWhen considering suicide rates, the importance of exploring it could potentially unravel the underlying societal issues like poverty, inequality, and insufficient mental health care. Furthermore, recent years have been critical in the progression of mental health care amongst individuals, which in turn could affect the prevalence of suicide rates in the world (Brådvik, 2018; Tao and Cheng, 2023). Furthermore, low-income countries often provide less priority to mental health concerns, as they typically face other socioeconomic issues for which the policymakers focus the issues prevalent in their society undermining importance of mental health care. n nThese economic downturns were further compounded by regional political conflicts, namely the Russian-Ukraine conflict, which disrupted the oil trade and increased essential commodity prices, leading to increasing economic instability. Typically, any country’s economy focuses on primarily the GDP to determine the standard of living of its citizens and unemployment and to determine how much of its healthy adult citizens contribute to the economy. Prominent research shows an interrelationship between unemployment and economic growth, often where studies depict a negative correlation among these factors (Claveria, 2022a). It implies that slower economic growth is typically intertwined with higher unemployment rates in a country. n nIn the modern world, it is crucial for any country to carry out trade activities namely, import and export, and most of the world countries engage in trade. Many countries are export heavy, where they invest the bulk of their economy into producing export of primary commodities particularly, food, electronics, and essential goods, which in turn generates revenue for them. In contrast,some countries are more import reliant for their primary commodities, however they have more refined exports namely, Integrated Circuits, Petroleum, Cars and Gold (Anwar et al. 2024). By understanding the interplay between export and import among the countries and the willingness of countries to invest their yearly budget into developing their trade infrastructure, it is possible to understand the influence of trade on the global economy. Given these challenges, an empirical examination of the interrelationship between economic uncertainty, suicide, unemployment, economic growth, and trade is timely and essential. Thereby, this study focuses on the following research and questions and objectives: n n(1) n nQuestion 1: How does economic uncertainty cause changes in suicide rates, unemployment rates, economic growth and trade openness in high uncertainty countries? n n(2) n nQuestion 2: How do the socio-economic variables affect economic uncertainty in high uncertainty countries? n n(1) n nObjective 1: To determine whether economic uncertainty cause changes in suicide rates, unemployment rates, economic growth and trade openness in high uncertainty countries. n n(2) n nObjective 2: To explore the impacts of the socio-economic variables on economic uncertainty with high uncertainty countries. n nThis study aims to contribute to the existing literature in the following ways. Firstly, this study identifies 30 countries with highest economic uncertainty based on the World Uncertainty Index (WUI). Where a significant gap exists in certain countries and their relationship to uncertainty is often largely unexplored. This study aims to bridge this gap by providing a comprehensive country level analysis. Secondly, it is noted that existing literature often explores how economic uncertainty affects socio-economic variables, utilising either one or two variables and often overlooking the bidirectional effects among the variables. Thirdly, this study utilises the Granger Causality and Cointegration Tests to identify the direction of relationship within the uncertainty and socio-economic relationship. While there exists studies utilising these methodologies, none have done so in unified context incorporating 5 variables. By analysing 30 countries over 23 years considering the socio-economic variables, this study applies these methodologies in a unique way providing novel findings. Fourthly, by identifying the causal and cointegrating relationships, this study provides valuable insights for policy makers. These policies are tailored to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The policies are aligned with SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being, SDG 4: Quality Education, SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure, SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities, SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals. Finally, this study contributes significantly to visualising aspects of studies with the use of modern analytical techniques to provide an eye-catching and comprehensive visualisation. n nThe paper is structured as follows: it begins with a critical review of existing empirical research, followed by a detailed explanation of the data collection methods and methodologies used. The empirical results are then presented and discussed, culminating in a conclusion that outlines the study’s essential findings and policy implications. n nThe relationship between economic uncertainty and socio-economic variables can be explored through various theoretical frameworks. Critical theories linking economic uncertainty and suicide rates are economic stress theory, which inspects the effects of inflation and financial instability on the mental well-being of people. Furthermore, Durkheim’s social integration theory suggests the level of interconnectedness among people has a crucial impact on suicide rates (Durkheim, 1897). However, when there is economic uncertainty, this often leads to the weakening of social ties and reducing the sense of community, which makes individuals more prone to suicide. n nWhen considering uncertainties and unemployment rates, the job search theory suggests that during uncertainties, unemployed workers are more cautious about venturing into new jobs due to the instability of future employment (Stigler, 1962). A prevalent theory in the field of strategic management is real options theory; the primary fundamental of this theory is that when firms face uncertainty, there is a reduction of investment into capital and labour (Myers, 1977). It is preferable to make decisions after a delay with more information. However, this delay often leads to fewer jobs, thus, creating higher unemployment. Theories suggest that economic growth, economic uncertainty and unemployment are linked, as robust economic growth allows for job creation and increases labour demand. In contrast, uncertainties lead to hire freezing and layoffs. n nEconomic uncertainty and economic growth are deeply rooted within each other in the modern era. However, theories regarding the interrelationships among them were formulated as early as the 1930s, and such a prominent theory is the Keynesian Economic theory. This theory suggests that economic uncertainty negatively impacts consumer and business spending, leading to reduced consumer consumption and business investment; this decline leads to economic (Keynes, 1936). The prospect theory examines how people take decisions when influenced by risk & uncertainty and suggests that people evaluate potential gains and losses relative to a reference point. Kahneman and Tversky (1979) proposed that people do not always maximise utility, in situations pertaining to uncertainty influencing individual and firm decisions. Endogenous growth theory suggests that during times of uncertainty, investing in innovation, research and development is discouraged, leading to a less stable future economy (Romer, 1986). When considering these theories, a negative relationship between uncertainty and economic growth can be identified, as uncertainty can reduce investment and consumption, which in turn reduces economic growth. n nIn the context of trade openness and economic uncertainty, there are key theoretical key concepts which link them, namely the transaction cost theory suggests that uncertainty can be avoided when the firm is well established and in contrary view, uncertainty also increases the transaction costs, including transportation; this leads businesses to invest in domestic markets, which are more predictable when compared to international markets (Coase, 1937). Tinbergen (1962) explores how countries engage in trade during periods of high uncertainty and factors influencing trade. Trade Policy Uncertainty (TPU) theory this suggests that uncertainty about future trade policies creates hesitation among the firms and their willingness to invest in international trade (Handley, 2014). The gravity model of trade predicts the flows bilateral trade flows between two countries based on their economic sizes. n nBy understanding these prominent theories, it is possible to determine the relationships that exists among these variables and the importance of how these variables interplay with each other can be identified. n nBased on the theories prevalent in the current global context, Fig. 1 depicts how the relationships among the variables are established. This provides a basic understanding of how these variables interplay with one another, aimed with this knowledge, a comprehensive analysis of existing literature is explored in the following section. n nThe following section examines the existing relationship between economic uncertainty, suicide rate, unemployment, economic growth, and trade for selected thirty countries with the highest economic uncertainty, providing a comprehensive context for this study. Appendix S1 shows the articles used for this study to determine the gaps in the research and for the identification of the variables. There is a significant number of articles for countries with high uncertainty particularly, Chile and South Africa, allowing us to develop our research based on existing empirical findings. Figure 2 showcases a region-wise breakdown of the countries from which articles were generated for this study’s literature. China, the United States, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Russia contributes significantly to the literature, allowing us to examine the key players in an international stage in context of academic research on uncertainty. n nEconomic uncertainty stems from day-to-day transactions, however it could cause significant disruptions in economic activities in todays’ interconnected world. These uncertainties also affect businesses, where during this period they refrain from making any major investments (Bernanke, 1983; Bloom, 2009; Bachmann et al. 2013), this leads a freeze in the growth of an economy however once uncertainty is reduced there can be a temporary boom caused by the rapid investments of businesses (Bloom, 2009). Another primary factor causing uncertainty is government decisions on fiscal and monetary policies, as shown in Turkey (Kasal and Tosunoglu, 2022) and United States (Fernández-Villaverde et al. 2015), businesses struggle with this uncertainty, causing an exacerbation of economic decline. Uncertainty has grown to be a major concern in the modern scholarly community where a variety of discussions are put fourth, these reviews are taken into account when identifying the relationship between the variables in this study. By thoroughly examining these relationships, the subsequent sections are utilised to identify existing gaps in the literature. n nRelationship between economic uncertainty and suicide n nEconomic uncertainty has transcended through geographical boundaries, impacting economies worldwide. Analyses conducted investigating this relationship in the global context (de Bruin et al. 2020; Claveria, 2022a, 2022b; Er et al. 2023; Tao and Cheng, 2023) reveals that economic downturns can have a detrimental impact on mental health, leading to the risk of suicide. n nEmpirical evidence highlights that economic uncertainty is a driver of suicide rates, particularly in economies with high performance (Antonakakis and Gupta, 2017; Vandoros et al. 2019; Vandoros and Kawachi, 2021; Abdou et al. 2022; Er et al. 2023; Sorić et al. 2023; Tao and Cheng, 2023; Goto et al. 2024; Lepori et al. 2024). Er et al. (2023) finds no link between low- and middle- income countries, however the West African region reveals a negative impact of uncertainty in low- and lower-middle income countries, contrasted by a positive long-term relationship in lower-middle income countries (Iheoma, 2022), another upper-middle income country: Turkey, indicates an association between uncertainty and suicide rates (Karasoy, 2024). n nUncertainty coupled with the effects of unemployment foster suicide rates in the United States (Antonakakis and Gupta, 2017). In contradiction to this Vandoros and Kawachi (2021) finds a statistically insignificant association between unemployment and suicide. n nThe COVID-19 pandemic stands out as major catalyst fuelling uncertainty. It exacerbates the negative effects of mental health (Lee and Nam, 2023) and induces anxiety, financial strain and suicidal thoughts (S. T. Khan et al. 2023). Additionally, the pandemic is a leading cause of suicide among youths (Bridge et al. 2023) and in the adult population (Nouhi Siahroudi et al. 2025). However, Yan et al. (2023) and A. M. Kim (2022) suggests that the overall rate of death by suicide remained basically unchanged but, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt were more prevalent. Further suggesting that the commonly shared thoughts that the pandemic’s impact would lead to an increase in suicides needs to be re-examined. n nA crucial theme in contemporary literature is that the analyses on suicide rates are conducted for male and female groups separately, with a much-pronounced effect on males (Antonakakis and Gupta, 2017; Vandoros et al. 2019; Abdou et al. 2022; Goto et al. 2024; Lepori et al. 2024). Accordingly, developing gender specific policies is crucial in mitigating uncertainty effects. n nRelationship between economic uncertainty and unemployment n nEconomic uncertainty plays a significant role in employment rates in the country, prompting researchers to examine its impact with studies generally indicating uncertainty has a positive impact on unemployment rates (Valadkhani, 2003; Caggiano et al. 2014; Payne, 2015; Caggiano et al. 2017; Schaal, 2017; Ahmed et al. 2022; Haldar and Sethi, 2022; Zaria and Tuyon, 2023). Youth employment in particular has been detrimentally affected by uncertainty (Dajčman et al. 2023). Uncertainties from one region of the world can have an impact on unemployment rates in another, as Dajčman et al. (2023) highlights, there is an effect of U.S uncertainties on unemployment rates of Germany, France, Italy and Spain. There are implications on types of uncertainty affecting unemployment in various ways, firstly, sectoral uncertainty has a stronger and lasting effect whereas, and aggregate uncertainty has a more immediate and transient effect (Choi and Loungani, 2015). Recent literature suggests COVID-19 to be a prime driver of unemployment rates (Su et al. 2021; T. Li et al. 2023), causing job losses across various sectors globally. Accordingly, while there causal flows in uncertainty and unemployment in the global context, a significant gap in exploring the bidirectional relationship between the two is noticeable. n nRelationship between economic uncertainty and economic growth n nEconomic uncertainty shapes the economic activity with the country, influencing its inhibition and contraction. The impact of uncertainty on economic growth in a global context has been explored by many researchers (Lensink et al. 1999; Lensink, 2001; W. Kim, 2019; Cepni et al. 2020; Phan et al. 2021; Bannigidadmath et al. 2024; Gómez and Cándano, 2024; Gomado, 2025). Uncertainty acts as an inhibitor for economic growth and expansion, exerting a pessimistic impact on the growth rates in economies for high uncertainty countries (Gu et al. 2021; J. Li and Huang, 2021). In a real-world context, the countries exist in an interconnected global economy, hence the issue of spillover leading to uncertainties in more developed nations to impact the economy of less developed countries (Cepni et al. 2020; Fernández and Antonio, 2021; Ekeocha et al. 2023). Consequently, nations with robust economic growth can exert considerable influence on countries with lower economic growth. n nEconomic growth and its’ uncertainty relationship can be measured using various methods, as economic growth is not limited to GDP increase, it can also be measured by tourism, foreign direct investments, total factor productivity, sustainable development which are indicators that can be utilised in determining a healthy economy. The current literature provides a solid foundation for these relationships where in all cases the effect of uncertainty is negatively associated with the variables (Liu et al. 2020; Amarasekara et al. 2022; Ogbonna et al. 2022; Gupta, 2023). Moreover, the effect of economic uncertainty is both present in the short term (Adedoyin et al. 2022; Wen et al. 2022) and the long term (Adedoyin et al. 2022; Ghosh, 2022). While these studies identify a relationship between economic growth and uncertainty, a study conducted by Gomado (2025) reveals that the quality of pro-market institutions reduce the negative effects of uncertainty. n nWhile the recent years have cause economic upheaval, with Brexit and deceleration of Chinese economy, but the COVID-19 pandemic had the most significant blow, exposing both developed and developing economies facing risks and uncertainties due to the effects of the pandemic (Njindan Iyke, 2020; Gozgor and Lau, 2021; M. Sun et al. 2024). The studies also find that the COVID-19 related deaths did not hinder GDP in advanced economies, however the lockdown restrictions had a more severe detrimental effect in emerging and developed economies (Gagnon et al. 2023). While the pandemic’s effects are detrimental if managed properly these uncertainties could also be mitigated as M. Sun et al. (2024) explains that the proactive measures adopted by China in response to the pandemic crisis played a pivotal role in effectively mitigating its detrimental effects on the GDP. However, there remains a gap in identifying the impact of economic uncertainty on economic growth in low-income countries. n nRelationship between economic uncertainty and trade openness n nWith trade openness considered a crucial factor in the modern world, the influence of economic uncertainty can disrupt supply chain and increase vulnerabilities in interconnected economies. Trade often tends to decline when there is a rise in uncertainty caused due to factors like geopolitical tensions, policy unpredictability and pandemics. When considering trade there are two key players China and the United States, they form a global trade network, however this also provides easier access for uncertainties to travel to unsuspecting nations (Tam, 2018; Abaidoo, 2019; Dogah, 2021). While the economic policy uncertainty affects exchanging of goods in nations showing strong negative relationship among them (Kirchner, 2019; Jory et al. 2020; Matzner et al. 2023; Younis et al. 2024). A study conducted by Handley (2014) found that TPU significantly reduces firm-level export growth which in turn creates protectionist measure, often a response to uncertainty. In addition to the effects of Chinese uncertainty on global markets, there is negative effect of overseas uncertainty on the Chinese markets affecting China’s exports (Wei, 2019; Fan et al. 2023). Moreover, TPU affects renewable energy consumption in U.S. and China (Qamruzzaman, 2024) disrupting supply chains for renewable energy technologies and deterring investments into green energy. n nWhen considering bi-lateral trade, a one unit increase in uncertainty declines trade by 4.4, also identifying that deeper trade integration mitigates the negative impact of uncertainty on trade and in contrast, higher participation in global value chains amplifies the negative effect of uncertainty on trade (Nana et al. 2024). Moreover, Barbero et al. (2021) suggests that there is a negative impact of COVID-19 on bi-lateral trade for countries that were included in regional trade agreements, with these negative effects being more pronounced when the countries share identical income levels and the highest impact being among high-income countries. n nData n nThe data for this study is obtained from a publicly available global database, with the use of secondary data, primarily covering a period of 23 years for a dataset of 30 countries. With some countries being excluded due to data limitations or missing data. There was a lack of data for certain years in a number of countries, hence, Linear Regression, Polynomial Regression, or Averages were used to fill in the missing values. This study uses a quantitative approach based on the countries with highest economic uncertainty for the year 2022. The data file used for this study is presented in the Appendix S2 and it includes 690 observations for the 23 years. The following Table 1 shows the sources from which secondary data was collected. n nWUI is measured by using Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) reports that provide forecasts for various countries, therefore, the frequency of the term “uncertainty” in these reports or its variants, if any, is analysed, and the report is calculated. This count is averaged over the total number of words in the record when calculating the length of the different records. The WUI cover 143 countries, including both advanced and developing economies and provides a broader scope making it versatile for analysing diverse uncertainty factors. This index also allows for capturing the interconnected nature of the global economy where uncertainty in one country can spill over to others, as evident with the COVID-19 pandemic. A primary advantage of the WUI is that it incorporates include consistent methodology for cross-country comparisons, providing a broad coverage of the countries and giving quarterly updates, which allows to get timely data. However, the WUI has its limitations, with the EIU reports being potentially biased sources and the lack of granularity in the data, meaning the data has been grouped, particularly different uncertainties have been aggregated to provide an overall uncertainty reading. n nMethodology n nThis study evaluates the causal and cointegrating relationships between economic uncertainty and socio-economic variables using the Granger Causality Test (Granger, 1969) and Cointegration Test respectively. The Granger Causality test has been used in similar contexts; (Jayawardhana, Anuththara, et al. 2023; Jayawardhana, Jayathilaka, et al. 2023; Kostaridou et al. 2024), and in Tourism (Rasool et al. 2021; Wijesekara et al. 2022), Healthcare (Man Sun et al. 2020; Difrancesco et al. 2023). The method is also extensively used in other disciplines, in the field of Geopolitics (Shao et al. 2024), Supply chain and Logistics (Ren et al. 2024; Wu et al. 2024), Sustainable development (Ren et al. 2023; Perera et al. 2024), and Climate change (Kumar et al. 2023) to provide better context on the causal relationships among the variables in these disciplines. While there have been modern panel causality methods, particularly Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012); Juodis et al. (2021), however these models assume cross-sectional independence, whereas there exists significant cross-sectional dependence, as established by the Cross-Sectional Dependence test. n nThe Cointegration analysis has been utilised in similar research contexts (Jumbe, 2004; Ketenci, 2010; Chontanawat, 2020), including environmental sciences (Duan et al. 2008; M. K. Khan et al. 2020), education (Babatunde and Adefabi, 2005), and engineering (Turrisi et al. 2022). Using two methodologies allows for a robust analysis providing short- and long-term insights into the relationship among variables. Figure 3 shows the research pathway through the course of this study, including a detailed flowchart showcasing the actions taken to achieve the objective of this study, with an emphasis on the empirical two analytical methods. n nThis study is based on the Granger causality analysis, which helps predict trends by analysing possible changes between variables. If X variable causes another Y, then past data on X should provide a more accurate prediction for Y than past data on Y alone. n n$${{WUI}}_{i,t}= mathop{ sum } limits_{k=1}^{ rho }{ beta }_{i}{{WUI}}_{i,t-k}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{k=0}^{ rho }{ theta }_{k}{{SR}}_{i,t-k}+{u}_{i,t}$$ n n(1) n n$${{SR}}_{i,t}= mathop{ sum } limits_{k=1}^{ rho }{ beta }_{i}{{SR}}_{i,t-k}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{k=0}^{ rho }{ theta }_{k}{{WUI}}_{i,t-k}+{u}_{i,t}$$ n n(2) n n$${{WUI}}_{i,t}= mathop{ sum } limits_{k=1}^{ rho }{ beta }_{i}{{WUI}}_{i,t-k}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{k=0}^{ rho }{ theta }_{k}{{UR}}_{i,t-k}+{u}_{i,t}$$ n n(3) n n$${{UR}}_{i,t}= mathop{ sum } limits_{k=1}^{ rho }{ beta }_{i}{{UR}}_{i,t-k}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{k=0}^{ rho }{ theta }_{k}{{WUI}}_{i,t-k}+{u}_{i,t}$$ n n(4) n n$${{WUI}}_{i,t}= mathop{ sum } limits_{k=1}^{ rho }{ beta }_{i}{{WUI}}_{i,t-k}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{k=0}^{ rho }{ theta }_{k}{{EG}}_{i,t-k}+{u}_{i,t}$$ n n(5) n n$${{EG}}_{i,t}= mathop{ sum } limits_{k=1}^{ rho }{ beta }_{i}{{EG}}_{i,t-k}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{k=0}^{ rho }{ theta }_{k}{{WUI}}_{i,t-k}+{u}_{i,t}$$ n n(6) n n$${{WUI}}_{i,t}= mathop{ sum } limits_{k=1}^{ rho }{ beta }_{i}{{WUI}}_{i,t-k}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{k=0}^{ rho }{ theta }_{k}{{TO}}_{i,t-k}+{u}_{i,t}$$ n n(7) n n$${{TO}}_{i,t}= mathop{ sum } limits_{k=1}^{ rho }{ beta }_{i}{{TO}}_{i,t-k}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{k=0}^{ rho }{ theta }_{k}{{WUI}}_{i,t-k}+{u}_{i,t}$$ n n(8) n nThe formulas (1)-(8) represent the individual causality among the variables WUI & SR, WUI & UR, WUI & EG, WUI & TO, where i denotes the countries and t denotes the period in years, u and k denote the error term and several lags, these equations are used to identify bi-directional effects. n nDicky-Fuller Unit Root Test n nThe study also utilised the Augmented Dicky-Fuller (ADF) tests to determine the stationarity of the variables. Dickey and Fuller (1979) shows that if the calculate-ratio of the coefficient is less than critical value from Fuller table, then it is said to be stationary. The null hypothesis of the unit root is rejected at either, 1%, 5% or 10% levels. n nLag length selection criteria n nAt the lag selection step, the number of lags for each variable was determined to identify the causal link between WUI, SR, UR, EG and TO. There are three selection criteria used for determining the optimal lag length: Moment Akaike information criterion (MAIC), Moment selection Bayesian information criterion (MBIC), and Moment selection Hannan and Quinn information criterion (MQIC). The Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model is used for the Granger causality test. The Vector Autoregressive Selection of Order Criteria (VARSOC) command in STATA is then used to determine the optimal lag length for the VAR model. The minimum value of any of these criteria is used for the selection of the optimal lag length. The MAIC criterion is shown to provide a balanced model fit without overfitting (Ng and Perron, 2001). Therefore, to determine the optimal lag length for this study, the selection was based on the MAIC. n nGranger causality test n nThe Granger Causality Test is conducted to determine the causal relationships among WUI and the socio-economic variables. The hypothesis considered for testing whether X Granger causes variable Y is as follows: n nH0: Past values of WUI do not help predict Socio-economic Variables. This means the coefficients of the lagged values of WUI in the equation for Socio-economic Variables are zero. n nH1: Past values of WUI help predict socioeconomic variables. This means the coefficients of the lagged values of WUI in the equation for Socio-economic Variables are not zero. n nH2: Past values of socioeconomic variables do not help predict WUI. This means the coefficients of the lagged values of socioeconomic variables in the equation for WUI are zero. n nH3: Past values of socioeconomic variables help predict WUI. This means the coefficients of the lagged values of socioeconomic variables in the equation for WUI are not zero. n nThe Granger Causality test is highly favoured by researchers due to its ability to explore the bidirectional causal effects between the variables. Prior to conducting the Granger causality results the logarithmic differences of the dataset for each country were generated, so that the data could be measured from a common scale. After the Granger causality test has been completed subsequently the stability of the model is tested to ensure reliability. To test for robustness of the model alternative lags were utilises with a lag added and reduced from the optimal lag specification to identify variations in empirical results. n nStability graphs n nBy utilising the stability graphs, it is possible to assess and visualise the stability of the model coefficients across the different samples, the primary aim is to determine whether the model’s parameters are consistent over time (Abrigo and Love, 2016). This is conducted after the Granger causality test has been completed, stability in the VAR model is verified by ensuring that all eigenvalues of the coefficient matrix remain within the unit (Lütkepohl, 2006). However, there were instances where the eigen value exceeded the circle, therefore, to make the eigenvalues lie inside the unit circle, a maximum of two differences were used ensuring stability of the results. n nCointegration tests n nThe cointegration test determines the relationship between two or more non-stationary variables that may individually show trends over time that might have a stable, long-run relationship with each other. The Cointegration analysis has been utilised in similar research contexts. Some key advantages of cointegration are the availability of Error Correction Models (ECM). The Westerlund test allows for the presence of structural breaks, thus accounting for external factors, namely economic crises or technological advancements. VECM rank test determines the number of cointegrating relationships that exist between a set of variables in a multivariate time series model, further giving insights into the cointegrating relationship among WUI & SR, UR, EG, TO. n nThe dynamics between economic uncertainty and socio-economic variables, particularly explored in Durkheim’s social integrations theory, real options theory, job search theory, Keynesian Economic theory, could be accurately tested using these methodologies to identify supporting or contrasting findings to these theories. While the study utilised these methodologies, the study also used MapChart, Jupyter Notebook and Excel for charting illustrations. The statistical analysis was conducted through STATA software. The next section carries out the empirical analysis, showing how the findings complement or contrast with existing literature whilst integrating discussion perspectives.