In 2025, the global trade landscape remains complex, shaped by evolving policies and shifting economic dynamics. Journalists play a crucial role in interpreting this complexity, translating research into actionable insights for policymakers and the public. During the National Press Foundation’s 2025 International Trade journalism fellowship, participants were introduced to the Atlas of Economic Complexity, a powerful data visualization tool developed by the Harvard Growth Lab.

Annie White and Sebastian Bustos from the Harvard Growth Lab explained the theoretical foundation of the Atlas, its methodology, and its practical applications. “Our tools are primarily designed for policymakers, but we know journalists also rely on them to bring stories to life through data,” White noted.

The Atlas draws from the UN’s Comtrade database, which compiles semiannual trade data from countries worldwide. The Growth Lab refines this data to enhance accuracy and usability, enabling users to explore thousands of products and services by name or trade code. It also tracks industry growth trends across multiple years for individual countries.

Bustos encouraged journalists to consider the broader historical context of economic development. He pointed out that significant economic growth has only occurred in the past 200 years, leading to disparities in income levels across regions. “A key question is how to replicate successful economic models across different countries,” he said.

The Growth Lab posits that technology is a central driver of these disparities. Unlike capital or institutions, technology is difficult to transfer across borders. Bustos outlined three ways journalists can analyze this:

1. Technology resides in tools — accessible without needing to understand how to build or repair them.

2. It is embedded in codes, formulas, and blueprints that can be replicated.

3. It involves expertise or “know-how,” which is the most challenging aspect to transfer.

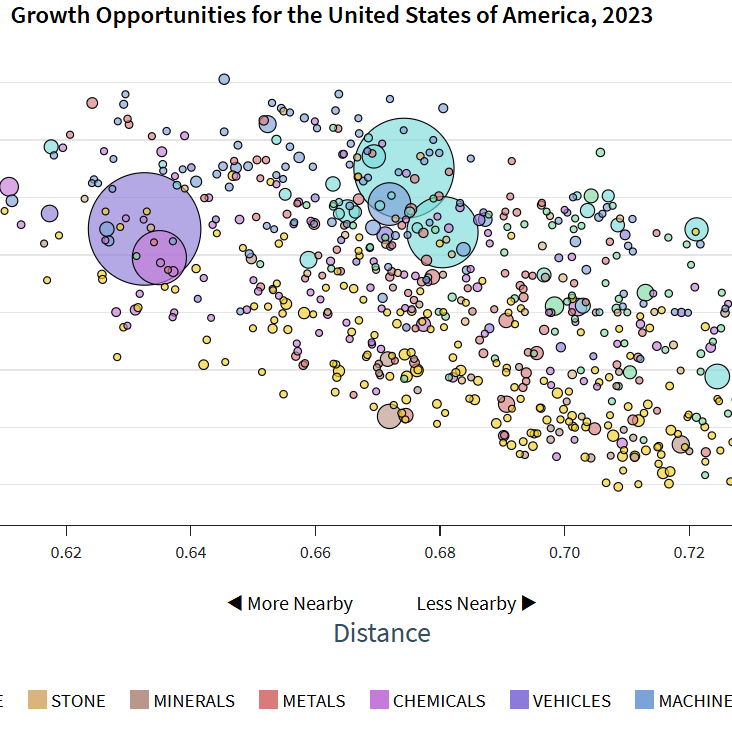

The Atlas allows journalists in 144 countries to explore their region’s economic profile. By analyzing what a country produces and how common those products are globally, journalists can better assess its economic potential.

The tool also generates country profiles and ranks nations using the Economic Complexity Index. In the latest ranking, Singapore topped the list. Bustos explained that deviations from expected economic performance can predict future growth. For example, countries like the Philippines and India, which are more economically complex than their current income levels suggest, are poised for strong growth.

— news from National Press Foundation

— News Original —

Harvard Growth Lab Ranks Countries on Economic Complexity – National Press Foundation

In 2025, the word “complexity” perfectly captures the status of global trade, now that the Trump administration’s tariff policies have dominated the international conversation of imports, exports, supply chains and deals.

But there is one immutable constant: journalists must understand and translate complex economic research to yield practical insights for policymakers and the public. National Press Foundation 2025 International Trade journalism fellows were briefed on the Atlas of Economic Complexity, a data visualization tool that provides insights into the economic capabilities and growth potential of countries around the world.

Annie White and Sebastian Bustos of the Harvard Growth Lab, unpacked the underlying economic theory behind the tool, the lab’s research approach and key features of the Atlas.

“Our tools have a wide reach, so we build largely for the policymaking community, but we know there’s a big cohort of researchers who use our tools as well and definitely journalists,” White said. “We find that the use case for our tools in journalism is really to make a story come to life through data visualization and really strong reliable data.”

Using data from the UN’s Comtrade database, which collects nationally reported data semiannually, the Growth Lab adjusts the data to maximize reporting, making it possible to chart thousands of products and services, searchable by name or specific trade codes. The atlas also shows the growth of industries in individual countries over multiple years.

While demonstrating some of the tool’s features, Bustos urged journalists to consider the historic scope of global economic development. He said it’s only been within the past 200 years or so that measurable, significant impact has occurred.

“What basically you see is that economic growth starts to happen, and we start seeing that there’s some divergence in the income capita across countries and regions in the world. A key question for us is how to think about what’s driving these differences and whether we can replicate the success stories across countries in order to unleash prosperity across cities, regions, and countries.”

The Harvard Growth Lab staff believes they know the answer.

“Our working hypothesis is that the driving force behind these differences across countries, it’s an issue of technology,” Bustos said. “Although capital institutions could be replicated across countries or distributed or shipped around and so on, technology is something that is very difficult to diffuse and replicate.”

Bustos offered three ways for journalists to analyze the central role of technology:

It resides in tools. “The key issue about tools is that there’s something that you don’t need to know how to produce. You don’t need to repair it or replicate it. It’s something that you need access to the tool and you need to know how to use it. This is a first way of thinking about technology.”

Technology is fueled by codes, formulas, blueprints or recipes. “You could have the technology needed to do a building or airplane and so on by looking at the tools and that’s something that in principle we can replicate.”

The third thing that makes technology hard to diffuse is training, expertise or “know-how.” “If it was an issue about tools, those can be shipped, if it was an issue about knowledge, we have all of the knowledge in scientific articles, Wikipedia and so on. All of the things have been written about. So the main issue that restricts this flow of knowledge across countries and explains the differences of productivity and at the end of prosperity across regions and countries is knowledge.”

When studying Harvard Growth Lab’s data, journalists must consider one central question for their own geographic regions: What is produced, and how ubiquitous are those products? An understanding of those factors can help predict a country’s income prospects.

The Atlas allows journalists in 144 countries to “choose their own adventure,” Bustos said. “What we’ve heard from people over the years is ‘can you just tell us the story of our country with a beginning, a middle and an end?’ And so that’s why we built country profiles.”

It also ranks countries based on the Economic Complexity Index. (In the most recent, Singapore ranked No. 1.)

“What we argue and we have shown in different papers is that these deviations from the trend are what is informative about future economic growth. And as you can see, for instance, we have countries above the trend like Greece that is a country that for the last 20 years has been in trouble. Our take on the case of Greece is that they are too rich for what they are able to produce.”

Then there are countries like the Philippines or also India. “In the last decades they have been doing great, they’re growing fast. And we believe that those countries are in essence more complex than the current income that they have. And that’s why the prospect that we see for those countries is great. We think that those countries are going to grow in the future.”