Nebraska’s Department of Economic Development has reduced its full-time workforce by more than 20 employees over the past two months, according to payroll data recently obtained by the media. Initially denying any layoffs, state officials later confirmed a decline from 112 full-time staff in September to 93 by November. Department spokesperson Justin Pinkerman stated that the reduction brought the number of filled positions to just over 90 by the end of November.

The administration now characterizes the downsizing as voluntary and part of a broader effort to scale back pandemic-era programs. Pinkerman explained that not all open roles are being refilled as part of efforts to improve operational efficiency. The department reached a peak of about 114 full-time employees by June 30 before beginning the drawdown.

Earlier claims from the Governor’s Office that no reductions occurred were revised after records from the Department of Administrative Services revealed the staffing drop. While officials maintain the cuts were not forced, former deputy director Joe Lauber said he was informed his role was eliminated due to budget constraints and was escorted out of the building in August, after 13 years with the agency.

Lauber recalled prior signs of fiscal tightening, including travel restrictions and hiring freezes. He also said interim director Maureen Larsen had communicated the governor’s intent to shrink the department through attrition—leaving vacancies unfilled when employees retire or resign. Strategies such as enforcing a strict 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. schedule and requiring employees to stay until at least 4:30 p.m. were reportedly used to encourage voluntary departures.

Larsen, who was later appointed permanent director, previously served as Gov. Jim Pillen’s general counsel. Critics, including union leader Justin Hubly of the Nebraska Association of Public Employees (NAPE), have questioned her appointment, suggesting she was brought in to lead a restructuring effort. Hubly noted that Larsen had minimal engagement with staff during her initial tenure, fueling perceptions of a top-down overhaul.

Other state agencies have seen similar reductions. The Department of Revenue laid off 11 agents, closed its Scottsbluff office, and downsized its Lincoln collections unit. Hubly criticized these moves, especially given State Auditor Mike Foley’s report that unpaid state taxes exceeded $310 million—an increase of 15% over the previous year.

At least four positions were cut from the Office of the Chief Information Officer, with smaller reductions across several departments. NAPE estimates about seven voluntary exits within DED between June and November, representing a portion of the overall decline.

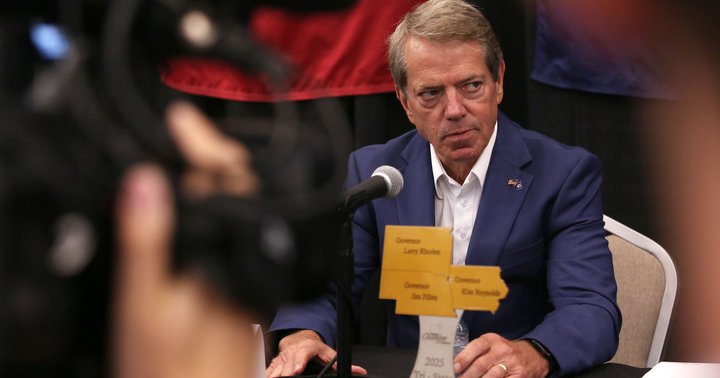

Governor Pillen aims to reduce the state’s two-year budget by $500 million by the end of the 2026 legislative session, with lawmakers facing a $471 million shortfall. Hubly urged the legislature to prioritize frontline services and explore alternatives such as new revenue sources or efficiency improvements rather than relying on workforce reductions. He warned that sustained cuts risk degrading service quality as remaining employees face heavier workloads.

— news from Nebraska Public Media

— News Original —

Nebraska Economic Development cuts 22 from full-time staff in 2 months

After state officials initially denied rumors of downsizing, Nebraska’s Department of Economic Development now acknowledges that it has paid roughly 22 fewer full-time employees over the past two months. n nSimilar workforce reductions have also impacted various other state agencies, prompting new concerns from some frontline workers that Gov. Jim Pillen and his administration are focusing on staff cuts to balance Nebraska’s budget. n nThe Governor’s Office initially claimed, in response to a reporter’s questions, that DED had seen “0 layoffs/reductions in force” through September and October, when the Examiner first asked in early November. n nThe state changed its tune after payroll records obtained by the Examiner from the Department of Administrative Services in recent weeks indicated 112 full-time employees on DED’s payroll in September, then 101 in October and 93 in November. n nJustin Pinkerman, a spokesperson for the Department of Economic Development clarified this week that DED was down to just over 90 filled full-time positions by the end of November. n nGovernor’s Office spokeswoman Laura Strimple amended her statement to say all of the reductions in full-time staff from September to November had been voluntary. And the department, via Pinkerman, now says the downsizing is part of a winding down of pandemic-era programs. n nLast month, Pinkerman had said DED eliminated only a single position this summer, that of Deputy Director of Operations Joe Lauber. n nThe DED downsizing comes as other cuts have impacted different state agencies, including the Nebraska Department of Revenue. The state laid off 11 revenue agents in October, closed the department’s Scottsbluff office and shrank its Lincoln-based individual income tax collections office. n nAt a press conference this week for a union representing state employees, the Nebraska Association of Public Employees, Executive Director Justin Hubly said reducing revenue agents when the state is short of funds was a “bananas decision” considering that State Auditor Mike Foley recently reported that unpaid state taxes had grown 15% over the past year, rising above $310 million. n nAdditionally, Hubly said at least four employees were cut from the state Office of the Chief Information Officer. He said smaller cuts have impacted several other departments in recent months. n nAt DED, evidence suggests that the majority of the downsizing was focused on managerial and higher-up positions not covered by union protections. Hubly said NAPE logged about seven voluntary departures within DED between June and November. NAPE represents roughly 55-60 DED workers, he said. n nLauber, who served as DED’s deputy director of operations and its chief legal counsel, said in August he was told his position had been eliminated due to budget cuts, and he was escorted out of the building. He had worked at DED for 13 years. n n“It came as quite a shock to me,” Lauber said of his dismissal. n nPrior to his termination, Lauber said there were signs of budget cuts impacting DED, like hiring freezes and directives to stop travel. He said during a management meeting he attended, then-interim director Maureen Larsen shared that it was the governor’s goal to reduce the size of DED through attrition. n nAgencies often do this by not filling positions people vacated through retirements and having or encouraging people to leave on their own. Lauber said the state implemented strategies such as Pillen’s return-to-work order and enforcing a strict 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. work schedule in hopes of getting people to consider whether they wanted to stay working for the department. Lauber said employees were not allowed to end their days earlier than 4:30 p.m. n nHubly said NAPE workers in other state agencies have also seen a pattern of the state cutting jobs this year to save cash. n nPillen has discussed his intent to cut Nebraska’s two-year budget by $500 million by the end of lawmakers’ 60-day legislative session in 2026. Lawmakers will enter the 2026 legislative session needing to fill a projected $471 million budget hole. n nHubly suggested the state implement retirement incentives as a way of tightening the budget, arguing that hiring younger workers would reduce staffing costs. Hubly said the governor rejected this proposal. n nPillen recently named Larsen the permanent DED director after she had served as interim director since July following former director K.C. Belitz’ resignation. Belitz did not return a request for comment. n nPrior to her appointment, Larsen served as Pillen’s general counsel and deputy director of his Policy Research Office. Hubly said he’s heard some concerns from workers that Larsen was appointed as director as part of a “hatchet job,” a term often used for someone hired to cut staff, due to a lack of outreach she did with the rest of the department. n n“We did hear a lot of concerns when she was kind of installed temporarily,” Hubly said. “She wasn’t out and about, she wasn’t introducing herself to people. So I think there was kind of this general consensus from people we talked to that was like, ‘She’s here to do a hatchet job and get rid of people.’” n nLarsen did not immediately respond to a request for comment. Pinkerman, reaching out on her behalf, said DED “experienced dramatic growth following the coronavirus pandemic.” n nPinkerman shared data showing that between 2020 to 2023, the department’s full-time staff grew by about 10-15 people per year. It reached a peak of about 114 filled full-time positions on June 30 of this year, which has since dropped to around 90. n nLarsen took over as interim DED director on July 21. n n“As DED winds down pandemic-era economic recovery programs and identifies greater operational efficiencies, not all positions that come open are being filled,” Pinkerman said in an email. n nHubly called on the Nebraska Legislature to protect frontline workers when debating budget adjustments this spring, arguing that staff cuts should be the last place state officials look to fill the deficit. n nInstead, he proposed searching for new revenue sources or surveying state workers for ways to improve efficiencies. n n“It is not possible to continually cut positions and increase workloads on state employees and not affect the quality of the services the employees provide,” Hubly said.