The importance of accurate and impartial economic data is gaining renewed recognition as governments and businesses rely on reliable statistics to guide decisions on fiscal policy, investment, and monetary management. Sound data serves as a foundational element for economic stability, enabling informed choices that affect millions.

A recent appeal by a former Greek government statistician has drawn attention to the vital role such data plays in democratic governance. His call emphasized that trustworthy figures act as guiding beacons, helping policymakers avoid economic pitfalls. Routine statistical work—often carried out by low-profile civil servants—provides essential insights into inflation, labor markets, and production, forming the backbone of effective decision-making.

For instance, central banks require precise inflation metrics before adjusting interest rates, while companies depend on dependable labor and energy cost data when considering new investments. Historical examples underscore the consequences of flawed statistics. In early 2000s Greece, underreported budget deficits contributed to a severe debt crisis and subsequent austerity measures. Similarly, Soviet agricultural data, manipulated to meet arbitrary targets, led to overestimated harvests and widespread famine.

In the United States, outdated models and inaccurate ratings of mortgage-backed securities played a role in the 2008 financial crisis. More recently, sharp revisions to employment figures sparked political controversy, highlighting how sensitive such data can be. Economists continue to advocate for the independence of statistical agencies to ensure integrity, regardless of political implications.

An updated System of National Accounts, endorsed earlier this year, aims to standardize how nations measure economic activity—including production, consumption, investment, and wealth. This global framework is being adopted worldwide to improve consistency and reliability. The need for modernization has been accelerated by technological advances; for example, one estimate suggests AI contributed nearly $100 billion in economic well-being in the U.S. last year—value not captured by traditional metrics.

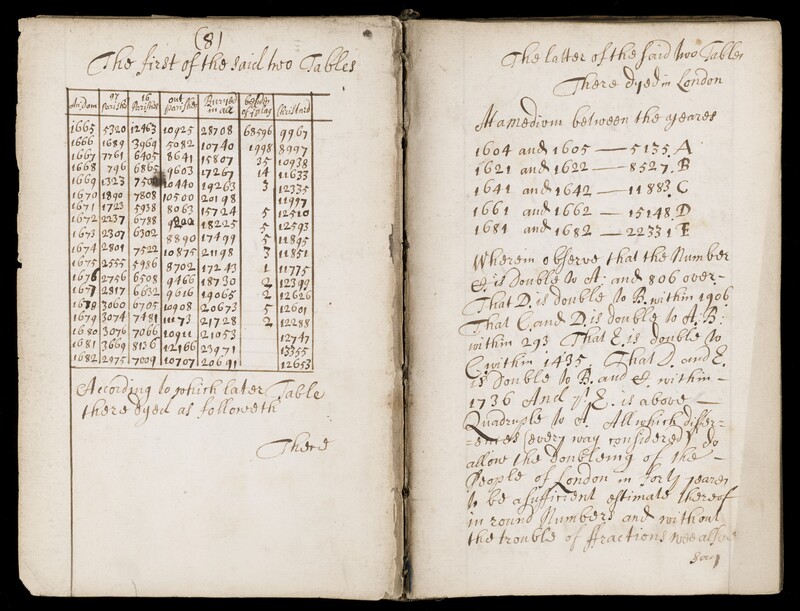

The roots of economic measurement trace back to William Petty’s 1690 work, “Political Arithmetick,” which promoted numerical analysis in economics. Since then, debates over data accuracy have persisted. Even today, revisions to U.S. jobs reports—based on ongoing business survey responses—are often misunderstood by the public, despite being a normal part of the process.

Transparency in methodology can help build public trust. However, challenges remain, such as declining survey response rates. In the UK, a sharp drop in responses once delayed a key jobs report, leaving policymakers without crucial information during a critical interest rate decision. Some officials have proposed making participation mandatory.

While unintentional gaps in data collection occur, deliberate manipulation has also marked history. Economic statistics are increasingly viewed as essential infrastructure—akin to a mirror reflecting reality. As one expert noted, no amount of political spin can alter the truth revealed under clear light.

— news from The World Economic Forum

— News Original —

What’s reliable economic data really good for, anyway?

The value of accurate and unbiased economic data is receiving renewed attention. n nBusinesses need solid figures to plan ahead, and public officials require them to make far-reaching decisions on spending and managing the money supply. n nHistory demonstrates that truth-in-data is oxygen for an economy. n nThe ancient Greeks knew a thing or two about democracy. So when a former government statistician from Greece recently made a plea to preserve something essential for “the functioning of democracy itself,” heads turned. n nThe subject of his juicy take? The very dry business of publishing trustworthy economic data. n nThe normally low-profile public servants who churn out tables and charts on a regular basis, and dutifully revise as needed, are illuminating lighthouses that prevent policy-makers from blindly crashing an economy on rocky shoals. n nShould we lower interest rates? Better have solid inflation figures on hand, or the decision may not deliver the desired results. How about investing in a new factory? Hopefully you have industrious clerks at the ready to provide reliable numbers on the local labour market and energy costs. n nWhen the ancient Greeks sought economic counsel, they turned to a guy strumming a lyre and reciting poems; Hesiod’s verse jibed with the labour theory of value, and was probably more enjoyable than a press release. It was also more accurate than the official budget-deficit figures modern Greece relied on in the first years of this century, which eventually turned out to have been under-reported. A worsened debt crisis and punishing austerity followed. n nOther historical examples of bogus information inflicting real damage include agricultural statistics in the Soviet Union often intended solely to hit arbitrary quotas. Political factions implemented a system liable to overestimate grain harvests, and contribute to famine. n nIn the US, a combination of outdated models and problematic ratings on the safety of mortgage-backed securities stoked the 2008 global financial crisis. More recently, that country’s jobs statistics became news – when a dramatic, downward revision to a pair of monthly figures aroused presidential ire. n nAs economists argue for maintaining the sanctity of data no matter whom it upsets, an international framework designed to help do just that is being revamped. n nAn updated System of National Accounts was approved earlier this year, and is wending its way around the world. It’s an international standard for measuring a country’s economic fundamentals: production, consumption, investment, and wealth. n nThe lofty benefits promised by technology made the need for a global measurement refresh more pressing. Nearly $100 billion in added economic well-being was enjoyed in the US alone last year thanks to artificial intelligence, according to one estimate – but none of that registered in traditional metrics. n nGetting the ‘arithmetick’ right n nThe British economist William Petty’s Political Arithmetick was published in 1690. It popularized the fledgling concept of applying numerical analysis to economics, and included its own sort of jobs report: “The Husbandman of England earns but about 4 s. per Week, but the Seamen have as good as 12 s.” People have been bickering about the accuracy of these kinds of figures ever since. n nThe same US labour-statistics agency that recently incurred the wrath of the White House also found itself in political crosshairs back in 2012. That time, it was an unemployment rate that seemed too good to be true. n n322 years earlier, Political Arithmetick sought to pre-empt any 17th-century political backlash with a preface carefully explaining that its overriding aim was “to shew the weight and importance of the English Crown.” n nIn the 21st century, some say it might be best to entirely remove the production of economic figures and other sensitive information from direct political supervision. The ex-Greek government statistician whose recent appeal for data integrity drew widespread attention certainly thinks so. He still faces legal action for his role in correcting the official record in his country more than a decade ago. Meanwhile the pain of subsequent austerity measures there has left a lasting imprint. n nOther suggestions for ways to bolster faith in economic data include better explaining the process behind it. US jobs reports provide a good example. Revisions to these numbers are nothing new, which is something most people don’t know. n nEach month’s new-jobs figure is based on surveys distributed to hundreds of thousands of businesses. It takes a while for many of them to respond. n nIn the meantime the initial data gets published even if it’s premature – but is then refined once the bulk of responses are in hand a few months later. A particularly big revision may signal a significant swing in the economy. It’s a bit like a journalist rewriting months-old copy at least a couple of times to get it right. Or, more right. n nAgencies may be able to better flesh out data like this for the public, but other aspects of the job sit further outside of their direct control. Like response rates. n nA few years ago, responses compiled for the UK’s benchmark jobs report plummeted so dramatically that its publication was disrupted. That left the country’s central bank in the dark as it sought to set interest rates, with billions of pounds for the economy hanging in the balance. Officials have since considered making responses legally mandatory. n nFalling short like that is one thing, fudging is another. Both are equally represented in the annals of history. n nEconomic data has been likened to vital infrastructure, and to a free information service for investors. The erstwhile Greek statistician who recently sounded an alarm chose to liken it to a mirror. Dim the lamp and preen all you want, but you’ll still look the same in the cold light of day.