The relationship between tourism and economic growth in Southeast Asian nations varies significantly depending on a country’s level of development, according to recent research. Two competing theories—the tourism-led growth (TLG) hypothesis and the economy-driven tourism growth (EDTG) hypothesis—offer different explanations for how these sectors influence one another.

The TLG model suggests that expanding tourism can stimulate broader economic development by generating foreign exchange, creating jobs, and encouraging investment in infrastructure and services. This effect is particularly pronounced in less industrialized countries such as Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, where tourism serves as a primary engine of growth. In these contexts, international visitor spending contributes directly to GDP and supports regional development, especially in rural areas. However, the benefits are not always evenly distributed, and rapid tourism expansion can strain local resources and infrastructure.

In contrast, the EDTG framework posits that economic advancement enables tourism growth by improving transportation networks, healthcare, and public services, making a country more attractive to visitors. This pattern is evident in more developed ASEAN economies like Singapore and Malaysia, where strong macroeconomic foundations support high-end tourism and global marketing campaigns. These nations benefit from both domestic and international travel demand, driven by rising incomes and robust infrastructure.

Empirical studies using Granger causality and structural equation modeling (SEM) reveal that bidirectional relationships exist in advanced economies such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore, where tourism and economic development reinforce each other. In less developed nations, the causality tends to be one-way, with tourism driving growth rather than the reverse.

The research analyzed data from 11 ASEAN countries between 2000 and 2023, using indicators such as GDP, international tourism receipts, human development index, and infrastructure quality. While the study focuses on international tourism due to data availability, it acknowledges that excluding domestic tourism may underestimate the sector’s full economic impact, particularly in countries where local travel is significant.

Policy implications differ based on development status. For less developed economies, targeted investments in tourism infrastructure could accelerate growth. For more advanced nations, maintaining economic stability and diversification remains key to sustaining tourism competitiveness. The findings also highlight the importance of sustainable models, especially in light of vulnerabilities exposed during the pandemic.

Emerging trends such as digitalization, medical tourism, and cultural revitalization are shaping recovery efforts across the region. Reports from the OECD emphasize the need for resilient, inclusive, and environmentally sound tourism strategies to ensure long-term viability.

— news from The World Economic Forum

— News Original —

Tourism-led growth or economy-driven tourism growth in Southeast Asian countries

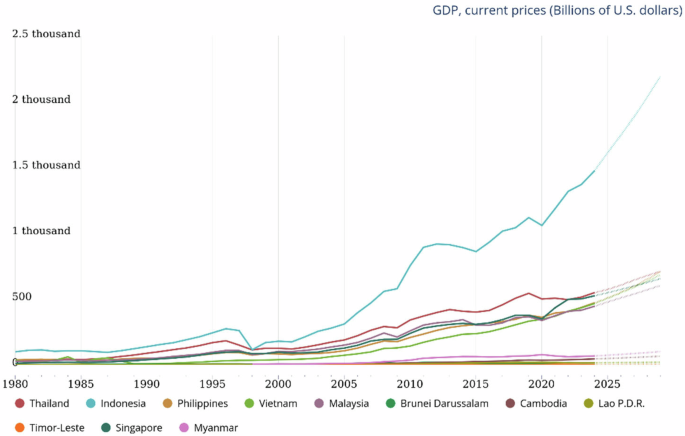

Tourism is acknowledged as a significant economic growth driver, enhancing various developmental aspects of a country (Etokakpan et al., 2019). As a service industry, it attracts capital, creates jobs, boosts foreign exchange, and fosters innovation. These benefits extend beyond tourism, positively impacting other industries through linkages that strengthen local economies. Due to its substantial multiplier effect, tourism is promoted by governments and supported by communities to improve economic conditions and infrastructure, reduce poverty, and increase employment. Investments in public infrastructure and foreign direct investment in tourism further enhance its potential to drive socio-economic progress. n nThe tourism-led growth (TLG) hypothesis, introduced by Balaguer and Cantavella-Jordá (2002), suggests a unidirectional causal link between tourism expansion and economic growth, proposing that a robust tourism sector can catalyze broader economic improvements. This hypothesis has prompted extensive research, with many studies validating it in various contexts. However, results are mixed; while some studies affirm that tourism can boost local economies and living standards, others report minimal or negative impacts, particularly in countries where tourism growth leads to infrastructure costs, environmental degradation, and reduced welfare (Akbarian Ronizi et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2024). n nConversely, the economy-driven tourism growth (EDTG) hypothesis posits that economic development can stimulate tourism growth (Cárdenas-García et al., 2024b). As economies expand, improvements in infrastructure, healthcare, and education attract tourists, especially business travelers. This hypothesis has been empirically validated, showing that the tourism-economic growth relationship varies with a country’s development level, tourism sector size, and market openness. Some regions or countries benefit from TLG, while others experience economic growth that drives tourism (Cárdenas-García et al., 2024b; Lin et al., 2018). n nThe varying results of the hypotheses underscore the complex relationship between tourism and economic development (Aslan, 2014). A systematic review by Brida et al. (2016) indicates that while the TLG hypothesis is confirmed in many studies, it is rejected in others, suggesting the relationship is not universal. Nation-specific factors—such as tourism industry size, economic openness, and production capacity constraints—are crucial in determining whether tourism drives economic growth or vice versa. Additionally, Cárdenas-García et al. (2013) show that this relationship’s dynamics differ significantly between high-income and low-income nations. Unlike earlier studies focused on global or generalized contexts, it highlights differences between more and less-developed ASEAN economies, revealing that tourism significantly drives growth in developed nations. In contrast, neither hypothesis strongly manifests in less-developed ones. The study’s use of advanced methodologies, including panel causality tests and structural equation modeling (SEM), allows for a deeper understanding of multi-dimensional relationships, surpassing traditional regression-based approaches. Additionally, it incorporates comprehensive indicators and recent data (2000–2023), reflecting post-pandemic dynamics and sustainable tourism challenges. These contributions offer fresh insights and tailored policy implications, differentiating this research from earlier works. n nIn recent decades, international organizations and scholars have promoted tourism as a tool for economic development, especially in developing regions (Ha Van et al., 2024; Y. Tang et al., 2025). However, critical research questions the assumption that tourism growth automatically leads to socio-economic progress. Rapid tourism expansion in some countries has resulted in significant local community costs, including environmental damage, overburdened infrastructure, and reduced welfare (Agarwal et al., 2023). These issues highlight the need for a nuanced understanding of the tourism-economy relationship, considering both benefits and limitations. Further research is needed to investigate the conditions under which tourism leads to economic growth and vice versa. n nFurthermore, the ASEAN region offers a unique context for studying the tourism-growth nexus due to its economic diversity, diverse tourism development levels, and varying industrialization stages (Mazumder et al., 2013). With countries ranging from high-income to lower-income, ASEAN serves as a natural laboratory for testing both TLG and EDTG hypotheses. However, previous studies have often treated the region homogeneously or focused on global panels, overlooking intra-regional heterogeneity. This investigation provides a timely and theoretically significant comparative perspective, identifying how different levels of development condition the directionality and strength of the tourism-growth relationship, enabling tailored policy recommendations for sustainable tourism and economic development across different ASEAN contexts. n nThus, the central question of this study is: How does the relationship between tourism and economic growth vary across ASEAN countries with different levels of development? To comprehensively address this, the study first tests whether tourism-led or economy-driven growth patterns exist across the ASEAN region. It then disaggregates the findings by development level, comparing less developed and larger economies to identify differences in the tourism and growth relationship. The study uses advanced econometric techniques to identify conditions under which tourism-led or EDTG occurs and explain these patterns across countries. The central hypothesis is that either tourism growth influences economic development in ASEAN countries or that economic growth stimulates tourism development. n nThis study makes several significant contributions to the literature on tourism and economic growth in ASEAN countries. Empirically, it is among the first to test both the TLG and EDTG hypotheses across all 11 ASEAN nations using a two-stage analytical design. This includes Granger causality tests for directionality and SEM for modeling latent multi-dimensional relationships. Differentiated modeling is another key contribution, as the study constructs two distinct models based on GDP categorization: one for all ASEAN countries (EDTG dominant) and one for larger economies (TLG dominant). From a policy perspective, the study highlights the economic vulnerabilities of over-reliance on tourism in larger economies, such as Thailand, while suggesting that targeted investment in tourism infrastructure could spur growth in less-developed nations. Methodologically, the combination of Granger causality, ARDL, and SEM provides a robust, multi-dimensional approach to understanding bidirectional relationships and latent variables, ensuring nuanced and context-specific findings. n nThe debate over whether tourism development stimulates economic growth or if economic growth fuels tourism has been the subject of numerous academic studies. The connection between tourism and economic growth in ASEAN nations is complex and differs depending on each country’s level of development. It is important to get closer to the two concepts: n nTourism-led growth hypothesis n nThis hypothesis posits that tourism development is a significant driver of economic growth (Shahzad et al., 2017). This theory proposes that a country can reap substantial economic benefits by attracting tourists. These benefits include generating foreign exchange earnings, creating employment opportunities, and stimulating various sectors of the economy, such as transportation, hospitality, and retail (Y. L. Liu et al., 2023; Y. Tang et al., 2025). The influx of revenue from tourism activities is believed to contribute significantly to overall economic expansion (Comerio and Strozzi, 2018; Seghir et al. 2015). As tourists spend money on accommodations, local products, and services, this expenditure circulates through the economy, potentially leading to increased investment, infrastructure development, and improved living standards for the local population (Cárdenas-García et al., 2024a; Seghir et al., 2015). Regions with less-developed economies, larger economic sizes, and larger geographic areas are more likely to experience TLG (Lin et al., 2018; Maganga et al., 2025; Quan and Wang, 2025; Zhang et al., 2025) n nTourism is crucial to the economies of ASEAN countries, contributing significantly to their growth (Var et al., 1999). Key studies in the ASEAN context have shown that Thailand and Malaysia, two well-developed tourism markets in ASEAN, demonstrate strong evidence for the TLG hypothesis (Jiranyakul, 2019; C. F. Tang and Tan, 2015). Tourism contributes substantially to their GDP, and their infrastructure and services are heavily integrated with the global tourism network (Wu and Wu, 2019). Indonesia and Vietnam, while developing their tourism sectors rapidly, show mixed results. Tourism boosts economic growth in some areas, while domestic growth fuels the expansion of tourism-related industries (Primayesa et al., 2019; Trang et al., 2014). In countries like Cambodia and Laos, tourism significantly impacts economic growth as they are less industrialized and rely heavily on tourism as one of their major sectors for development. Their economies depend more on tourism revenues than larger ASEAN economies (Kyophilavong et al., 2018; Law et al., 2022). n nTourism promotes economic development through foreign exchange earnings, employment generation, infrastructure investment, and regional development spillovers (H. Liu et al., 2021; Y. Liu et al., 2022). In ASEAN, tourism’s development function is evident in countries with limited industrial bases, where tourism represents a comparative advantage for growth (Kyophilavong et al., 2018). Tourism catalyzes development by encouraging public-private partnerships, improving transport and digital infrastructure, and fostering cultural and creative economies (Li and Sohail, 2023). For instance, Cambodia’s and Laos’s rapid tourism expansion has generated localized economic growth, even if national-level benefits remain uneven (Law et al., 2022; Nonthapot, 2016). n nBeyond direct income, tourism improves human development indicators, including literacy, healthcare, and life expectancy, due to increased government revenues and FDI (Ma and Tang, 2023; C. F. Tang and Tan, 2013) It also promotes regional equity by channeling growth into rural or underdeveloped areas, aligning with SDGs related to poverty reduction and inclusive development (Dai, 2025). n nUnlike traditional industries, tourism leverages local culture, heritage, and natural capital, often requiring lower initial investment while offering high employment elasticity (Y. L. Liu. 2023). This makes it a particularly effective development strategy for ASEAN’s less-developed economies. However, the extent to which tourism promotes sustainable development depends on governance quality, tourism leakage levels, and the ability to manage growth pressures. n nEconomy-driven tourism growth hypothesis n nThe EDTG hypothesis posits that a country’s economic development is crucial in fostering tourism growth (Cárdenas-García et al., 2024b). As economies expand, they typically invest in critical infrastructure, such as transportation networks, telecommunications, and hospitality facilities, essential for supporting a thriving tourism industry (Rehman Khan et al., 2017). This improved infrastructure not only enhances the accessibility and comfort for tourists but also creates a more attractive destination overall. Furthermore, economic growth often leads to increased government spending on tourism promotion and marketing efforts, which can significantly boost a country’s visibility in the global tourism market (Dimitrios Stylidis et al., 2022). n nThe relationship between economic growth and tourism development is multifaceted. Stronger economies tend to have a more stable political environment, better healthcare systems, and higher living standards, all contributing to a country’s appeal as a tourist destination. Additionally, as disposable incomes rise within a country, domestic tourism often experiences a surge, further stimulating the tourism sector (P. D. Adams and Parmenter, 1995). Conversely, regions with less developed economies may struggle to attract international visitors due to limited resources for tourism development and promotion. This disparity highlights the importance of economic growth as a precursor to tourism development, particularly in emerging markets and developing countries (Lin et al., 2018). The EDTG hypothesis thus underscores the need for comprehensive economic policies that can indirectly benefit the tourism sector through overall national development. n nThe larger economies of scale bring more profits to the tourism industry in ASEAN countries (Mazumder et al., 2013). In more advanced economies like Singapore, there is more substantial evidence for EDTG (LEE and Ging, 2008). These countries have strong economies that can fuel tourism by building world-class infrastructure, investing in marketing campaigns, and providing services that attract high-spending tourists. For instance, Singapore’s advanced economy allows it to maintain a leading position as a regional tourism hub, with the government supporting tourism through investments in infrastructure and global tourism campaigns. n nComparative synthesis of TLG vs. EDTG n nThe comparison between the two hypotheses, TLG and EDTG, highlights distinct causal directions and mechanisms (see Table 1). TLG posits that tourism drives economic growth through foreign exchange, job creation, and infrastructure development, with stronger empirical evidence in tourism-dependent or developed economies like Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore. Conversely, EDTG suggests that economic growth fuels tourism by increasing income, infrastructure, and services, with stronger evidence in emerging or industrializing economies such as Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Policy implications differ, with TLG advocating for investment in tourism sectors, while EDTG recommends strengthening the overall economy to boost tourism. n nVariations in tourism and economic growth dynamics across ASEAN n nThe contrast between the two hypotheses is presented in Table 1. Besides, tourism and economic growth dynamics differ between less developed and larger ASEAN economies. In less developed economies (e.g., Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar), these countries tend to rely more heavily on tourism to drive economic growth. A study of 8 ASEAN countries from 2000 to 2012 found that international tourist arrivals significantly affect economic growth, supporting the TLG hypothesis (Anggraeni, 2017). Tourism is key in providing foreign exchange, employment, and regional development (Adeleye et al. 2022). The lack of industrialization and weaker domestic markets means that tourism can profoundly impact their overall economic development. Tourism is often prioritized as a pathway to economic growth due to its ability to attract foreign investment and international exposure. However, the impact of tourism on economic growth varies among these countries. In the Greater Mekong Sub-region, including Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, international tourism spending on transport mediates tourism’s contribution to GDP and growth (Nonthapot, 2016), underscoring the need for transport sector development. Interestingly, while Cambodia has one of the highest annual tourism growth rates globally, the impact of the tourist industry on its economy remains relatively low (Chen et al., 2008). n nTourism often grows alongside economic development rather than driving it exclusively in the larger and more developed economies (e.g., Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia). Economic diversification allows them to develop tourism sectors that complement other economic drivers (e.g., finance, manufacturing, and services). Larger economies tend to benefit from both domestic tourism growth, driven by rising income levels, and international tourism, supported by superior infrastructure and government initiatives. For instance, these countries are part of ASEAN, representing only 1.5% of the world economy but growing faster than the global average (Hill, 1994). This indicates that their economic growth is not solely dependent on tourism. n nAdditionally, countries like Thailand are exploring ways to leverage sports event tourism to enhance their economic development (G. B. Williams et al., 2021), demonstrating a diversified approach to economic growth that includes but is not limited to tourism. Interestingly, the TLG hypothesis in Malaysia is not universally applicable to all tourism markets. A study found that only 8 out of 12 selected tourism markets, mostly from developed countries, significantly drive Malaysia’s economic growth (C. F. Tang and Tan, 2013). n nSeveral empirical studies use econometric techniques like Granger causality tests and cointegration analysis to examine the causal relationship between tourism and economic growth in ASEAN countries. Findings show that bidirectional causality exists in more developed economies like Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand, where economic growth and tourism development feed into each other (Holik, 2016). In less developed economies like Cambodia and Laos, the relationship tends to be unidirectional, with tourism leading to economic growth rather than the other way around (Kyophilavong et al., 2018; Wu and Wu, 2019). Thus, in conclusion, both hypotheses hold in ASEAN countries, but their relevance depends on the country’s level of development. Tourism is a critical driver of growth in less developed economies, while in more developed economies, economic growth supports and enhances the tourism sector. n nIt is noted that recent literature on tourism in Southeast Asia highlights both the vulnerabilities exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the region’s multifaceted pathways to recovery. Adams et al. (2021) underscore that while the pandemic placed countless tourism-dependent lives in limbo, local actors have demonstrated resilience through livelihood diversification, ecosystem regeneration, cultural revitalization, and the promotion of domestic tourism. These practices are deeply rooted in historical and place-based contexts, suggesting that resilience in tourism is not merely reactive but shaped by longstanding socio-political and cultural dynamics. Complementing this perspective, Chattoraj and Chin (2024) provide a broader regional overview, noting that the tourism sector—once a major economic driver employing millions, especially women in SMEs—was severely impacted by the pandemic, with significant job losses and the near-collapse of the informal tourism economy. However, recovery is underway, albeit slowly, due to global uncertainties and reduced Chinese outbound tourism. Emerging trends such as digitalization, food tourism, and medical tourism are reshaping post-pandemic travel, offering scholars and policymakers critical insights into how Southeast Asia’s tourism landscape is evolving in response to both internal adaptations and external pressures. Building on these discussions, the OECD Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China, and India 2023 (OECD, 2023) emphasizes the role of tourism as a key pillar of economic recovery, projecting that the full removal of travel restrictions will reinvigorate growth in the sector. The report stresses the urgency for Southeast Asian economies to adopt sustainable tourism models and strengthen sectoral resilience to future shocks. Collectively, these studies stress the need for historically informed, locally grounded, and digitally integrated approaches to rebuilding tourism in Southeast Asia. n nVariables and data collection n nVariables n nThis research examines the relationship between tourism growth and economic development in ASEAN countries, assessing whether tourism serves as a tool for economic development. Key economic indicators include the human development index (HDI), life expectancy, healthcare access, GDP per capita, infrastructure, and literacy rate. Tourism growth is measured through international tourist arrivals, tourism receipts, and related expenditures. These variables are crucial for SEM and Granger causality tests to analyze the complex relationships and causal effects between tourism and economic development. n nData collection n nThe study uses data from reliable sources such as the United Nations, World Tourism Organization, World Bank, and Asian Development Bank (see Tables 2 and 3). Tourism growth data covering economic contributions since 2000 allow for cross-country comparisons. Meanwhile, economic development data provide broader insights beyond growth. n nHowever, this study focuses solely on international tourism indicators, excluding domestic tourism due to data limitations across ASEAN countries. International tourism often has different economic impacts compared to domestic tourism, as it typically involves higher spending per visitor and contributes significantly to foreign exchange earnings. By not including domestic tourism, the study may overlook substantial economic contributions from local tourists, potentially underestimating the overall impact of tourism on economic growth. This exclusion could also skew the results, particularly in countries where domestic tourism is a significant component of the tourism industry. Additionally, the reliance on international tourism data may limit the generalizability of the findings, as the dynamics of domestic tourism can differ significantly from international tourism. Future research should consider incorporating domestic tourism data to provide a more comprehensive analysis of the tourism-economic growth relationship and to address these limitations. n nDespite some minor limitations, these consistent sources and variable options still ensure accurate and reliable data for SEM and Granger causality tests. This supports a credible analysis of tourism’s impact on economic development in ASEAN countries. n nLess developed economies and larger economies n nBrida et al. (2023) categorized Singapore as having high tourism specialization and high economic development; Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Vietnam as having low tourism specialization and low economic development; while Thailand has low tourism specialization and alternates between a high and low level of development (Cárdenas-García et al., 2024b). However, our study grouped 11 ASEAN nations into two categories based on IMF GDP data (Fig. 1 and Table 4). The less developed economies—Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Timor-Leste—have lower GDP and slower growth. In contrast, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam show higher GDP and faster growth. This division enables nuanced analysis and tailored policy recommendations for each group’s economic context. n nOur analysis follows a two-phase approach. First, we use time series analysis to identify TLG and EDTG in ASEAN countries, comparing general trends with those in less and more developed ASEAN nations. Second, we apply SEM analysis to examine the factors driving these models and their distinct influences. n nARDL causality test n nWe selected two key variables: one measuring tourism development and the other measuring economic growth. The measurements adopted in this study align with most past literature (Anggraeni, 2017; Var et al., 1999; Wu and Wu, 2019). The tourism revenue (ITR) is the international tourism revenue of ASEAN countries in USD at the current price. We measured economic growth at current prices as the real gross domestic product (GDP) in USD. We used real terms for all variables, which were expressed as natural logarithms using data from 11 countries in ASEAN. All data were obtained from the World Bank and United Nations World Tourism Organization from 2000 to 2023. n nThe ARDL model can be specified as follows: n n$${{ rm{GDP}}}_{t}={ alpha }_{0}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{i=1}^{p}{ alpha }_{i}{{ rm{GDP}}}_{t-i}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{j=0}^{q}{ beta }_{j}{{ rm{ITR}}}_{t-j}+{ in }_{t}$$ n n$${{ rm{ITR}}}_{t}={ gamma }_{0}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{i=1}^{p}{ gamma }_{i}{{ rm{ITR}}}_{t-i}+ mathop{ sum } limits_{j=0}^{q}{ delta }_{j}{{ rm{GDP}}}_{t-j}+{ nu }_{t}$$ n nWhere: GDPt is the gross domestic product at time t. ITRt is the international tourism revenue at time t. p and q are the lag lengths. n nWe analyzed correlation coefficients to examine associations and check for multicollinearity. Stationarity was tested using Levin-Lin-Chu, Im-Pesaran-Shin, Fisher ADF, and Fisher PP tests. After determining the integration order, we employed a cointegration model to assess long-term equilibrium relationships among non-stationary variables. Using the ARDL bounds testing approach (M. Pesaran and Shin, 1995), which accommodates mixed integration orders, we selected optimal lags via the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (M. Pesaran and Shin, 1995). The F-test and t-test assessed the null hypothesis of no long-term relationship. Lastly, the Granger causality test identified whether variable lags significantly influenced others (Shojaie and Fox,